Most of Open Syllabus’s work is built on citation analysis — on the ability to determine what’s taught and what’s taught together.

But syllabi contain a lot of other information about teaching and learning. For the past two decades, the coin of the realm in many areas of higher ed has been the ‘learning outcome,’ conceived as a way to abstract from course contents to an enumerated set of learning goals. Sometimes these are very concrete and specific to a topic:

Sometimes they describe very broad sets of competencies:

Often, individual learning outcomes are parts of larger frameworks that cover the range of required knowledge for a program or degree. In other cases, faculty rely on learning outcome guidance (such as Bloom’s taxonomy) to develop sui generis outcomes for their classes. With a few exceptions, learning outcome frameworks in the US and Canada are defined locally, at the individual program level. This has the advantage of keeping faculty engaged with the frameworks and of keeping outcomes closely tied to student needs. It has the disadvantage, however, of making them useless for comparative or system-level understanding of the curriculum, and for solving problems that require such perspectives. One example of the latter that we’ve been working on is course transfer, in which the lack of common frameworks for understanding class outcomes makes it difficult to establish equivalence between classes.

There are, according to the Lumina Foundation, over 3000 learning outcome frameworks in use in the US. Despite some notable efforts to organize this vast array of material, incentives for programs and schools to pool or coordinate learning outcome development remain weak. Because learning outcomes are generally present in syllabi, however, we may be able to reconstruct the learning outcome landscape from the bottom up. A national map of learning outcomes — in fact, an international map that includes frameworks from Canada, the UK, and the EU — may be possible.

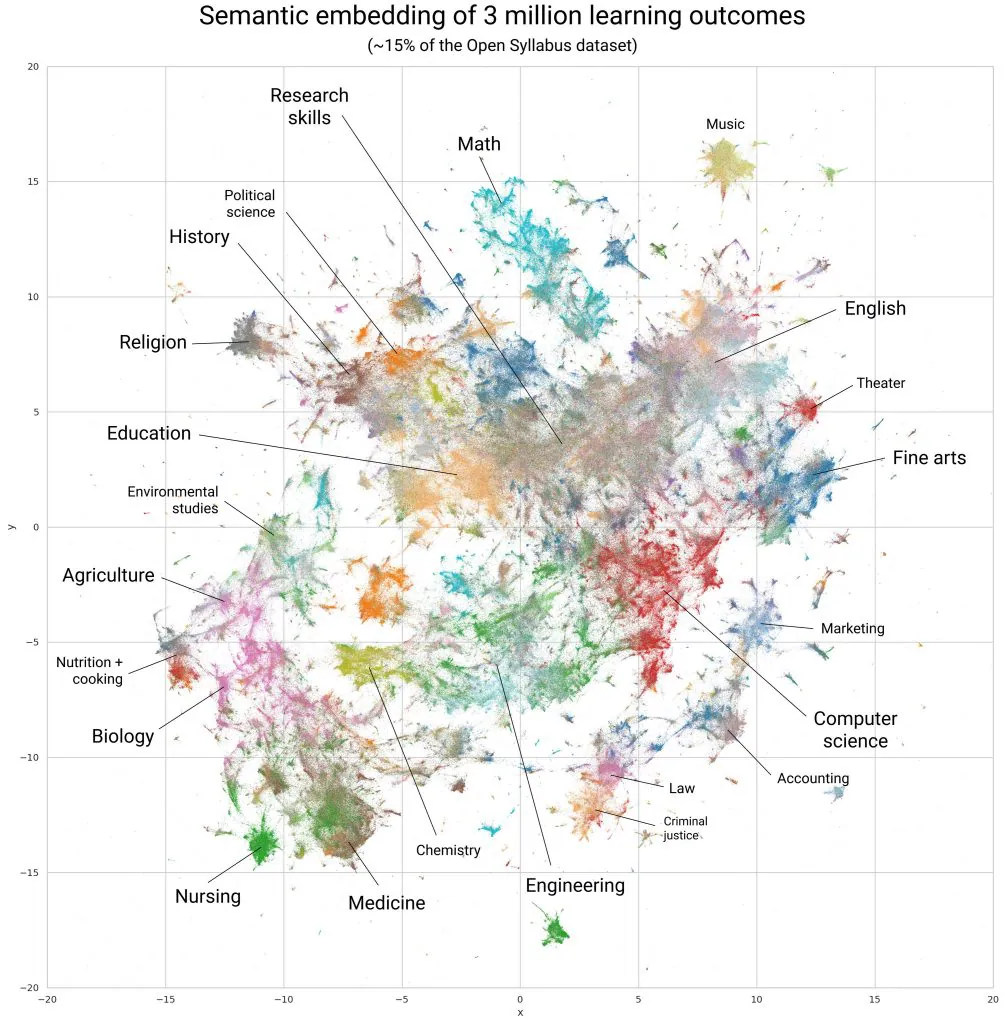

We can now pretty reliably extract the individual learning outcomes in syllabi. Our full dataset (currently 10.5 million syllabi) contains around 20 million unique learning outcomes. These can be compared semantically to generate a galaxy-style ‘map’ of the learning outcome landscape — here based on a sample of 3 million learning outcomes.

This is preliminary work that builds on relatively simple methods. But it has some interesting features. That wide grey band that runs through the humanities and social sciences suggests a lot of commonality to the learning outcomes in those fields, whereas the sharper boundaries in most STEM and practitioner fields imply more learning outcomes built around field-specific knowledge.

Overall, the graph shows enough definition to make us think that we can reverse-engineer a lot of the structure of the underlying frameworks. It won’t be a perfect map, but even a decent one would be leagues better than anything currently available and potentially make possible some of the system-level research and applications that were part of the original promise of learning outcomes.