With the release of the 2.13 dataset, we can update our analysis of OER adoption for 2024. You can see the ealier 2023 update here and here for 2022. And as always you can explore all of this in Analytics with a trial account or subscription.

To revisit some of the earlier context:

A few years ago we reported on the rates of growth in the adoption of ‘Open Educational Resource’ (OER) textbooks and ‘Open Access’ (OA) monographs. These are books published under Creative Commons licenses, which means that they can be used and circulated freely. In a world of $200 commercial textbooks, OER textbooks, in particular, have become an important part of school and state efforts to reduce student costs. But free has a few drawbacks. In markets for commercial textbooks (and most other goods), supply and demand are connected by the sale. Producers and consumers communicate through this information loop, and this relationship makes the market more or less efficient and — on the supply side — capable of adjusting. The information loop for free digital books, on the other hand, isn’t closed. There is no sale or single point of access and titles are copied and circulate freely. It’s hard, accordingly, to know what the demand side of the OER and OA ecosystems looks like. And this lack of information becomes a problem for authors and publishers (the producers) and faculty and students (the consumers). Decisions to invest time and money by faculty, funders, libraries and others in creating new titles are made without strong insight into the demand for existing ones. Adoption decisions by faculty and staff are made without much visibility into the experience of other programs, which could provide models. Both sides of the equation involve risks, that those risks are hard to mitigate. Open Syllabus can construct this demand side information from syllabi, and so partially close the information loop.

So what's new?

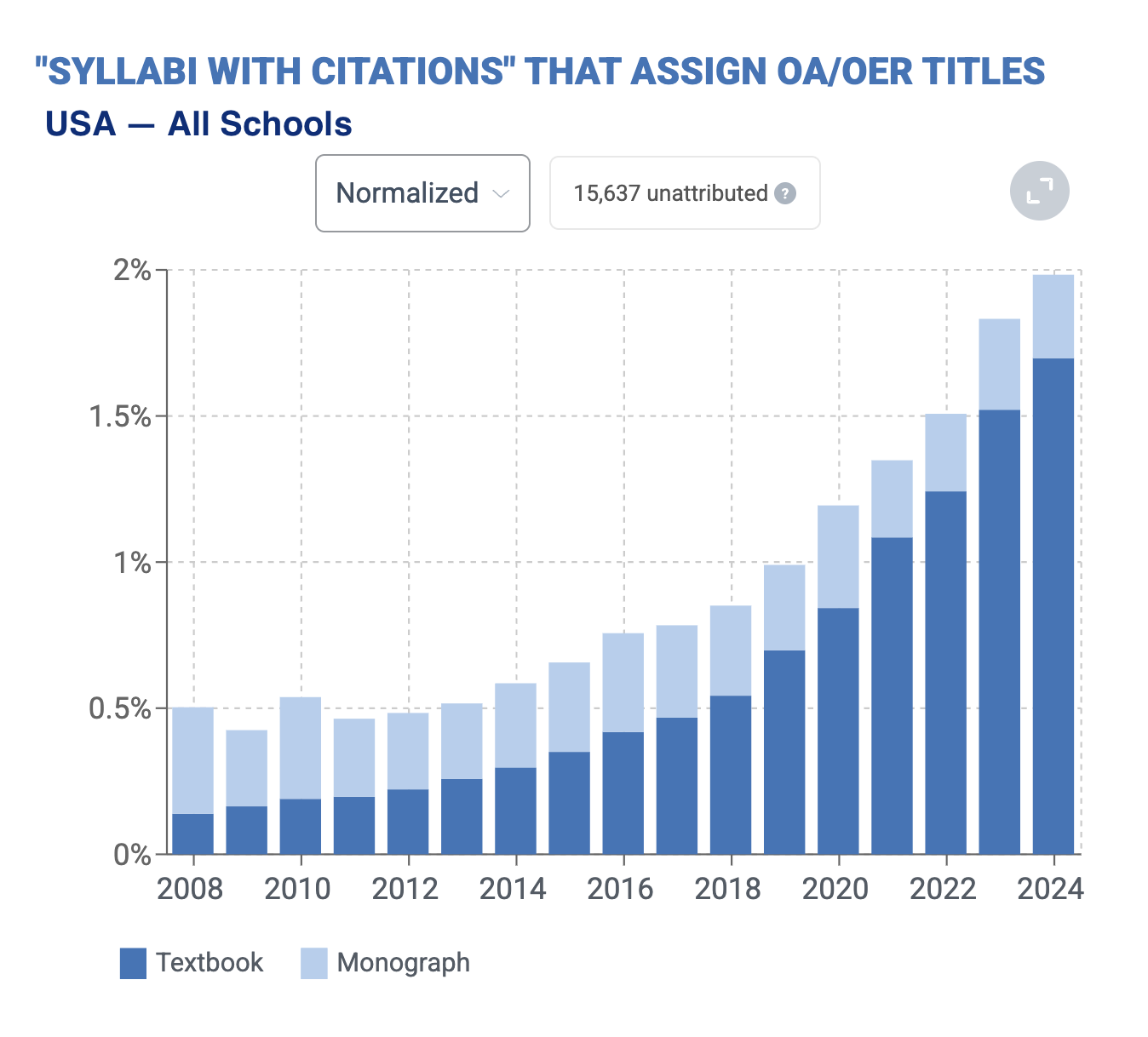

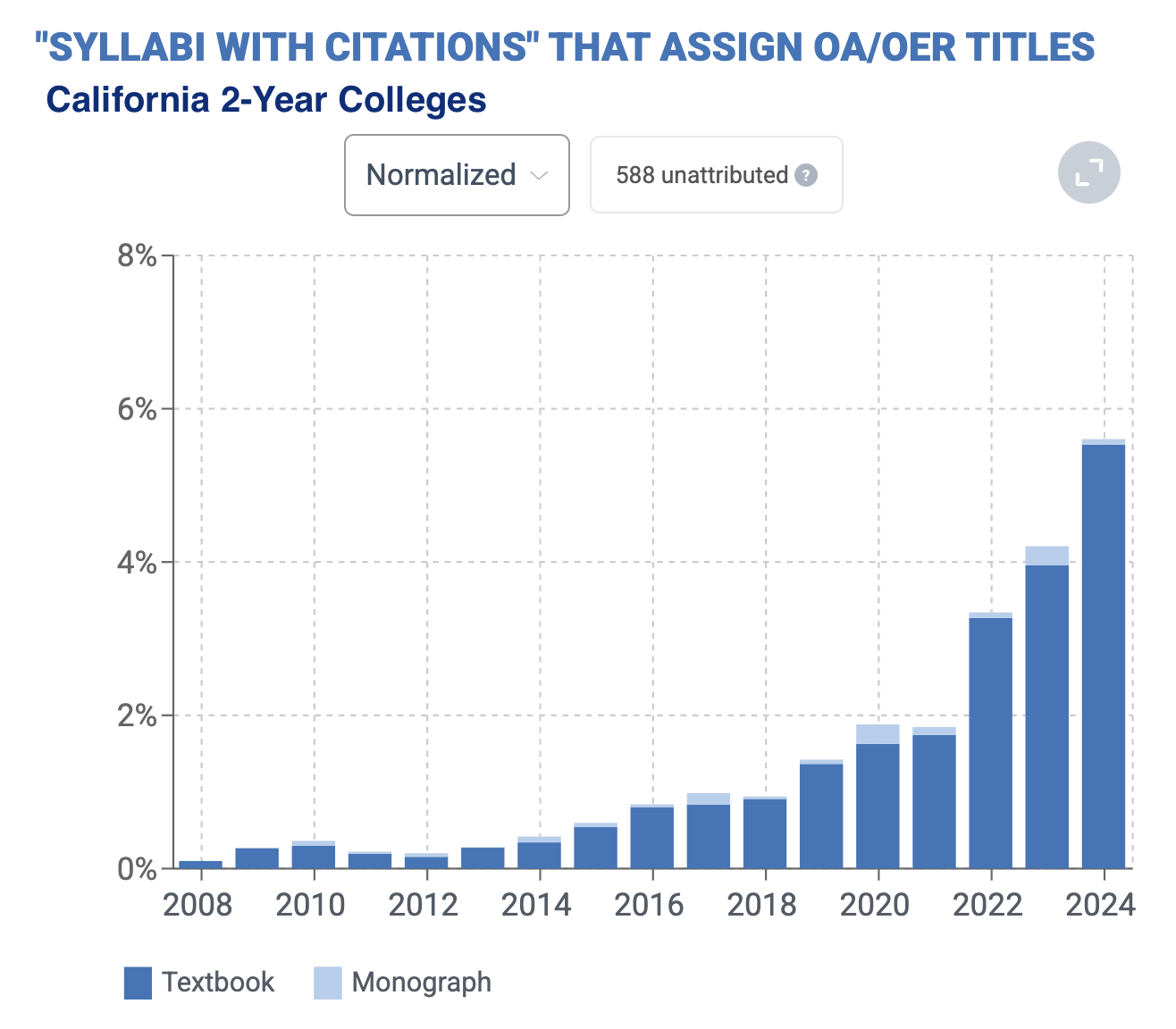

US data shows continuing growth of over 20% annually, with open titles now assigned in over 2% of all classes. The overall story is still one of fast growth but from a near-zero baseline in the mid 2010s -- and with a lot of variation by field and school type.

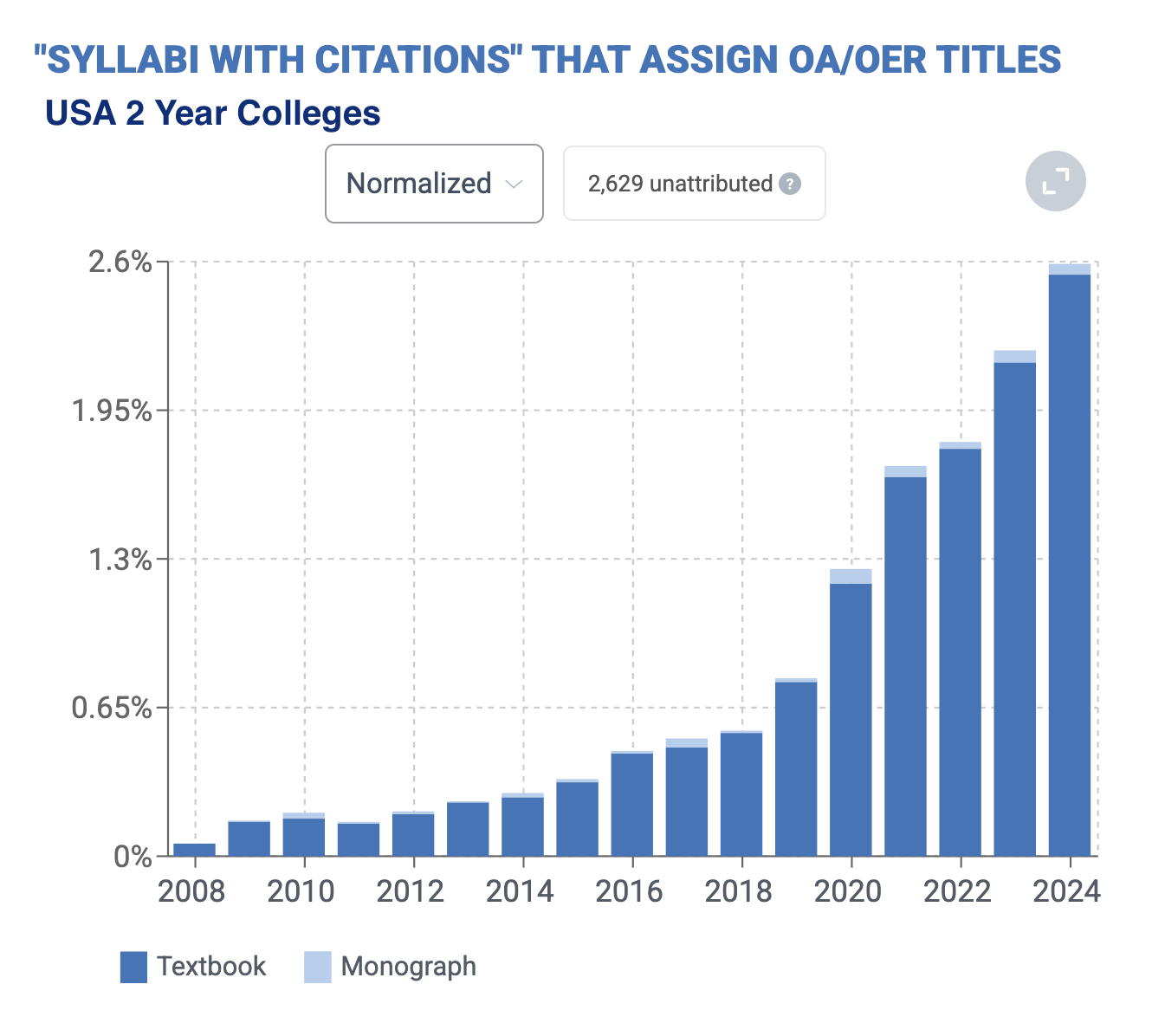

US adoption is primarily about textbook adoption — especially into the general education curriculum and especially at two-year colleges, which have been the focus of a number of state-level adoption efforts. Rates of OA monograph adoption, in contrast, have remained nearly unchanged over the period. We would attribute this to the much greater opportunities to scale up adoption of introductory textbooks compared to specialized scholarly work — though this pattern does not hold up consistently in other countries.

The fastest growth that we can measure is still in the California 2-year system, which benefits from the largest state-supported adoption program in the country. Nearly 6% of Calfornia 2-Year college classes use OER textbooks.

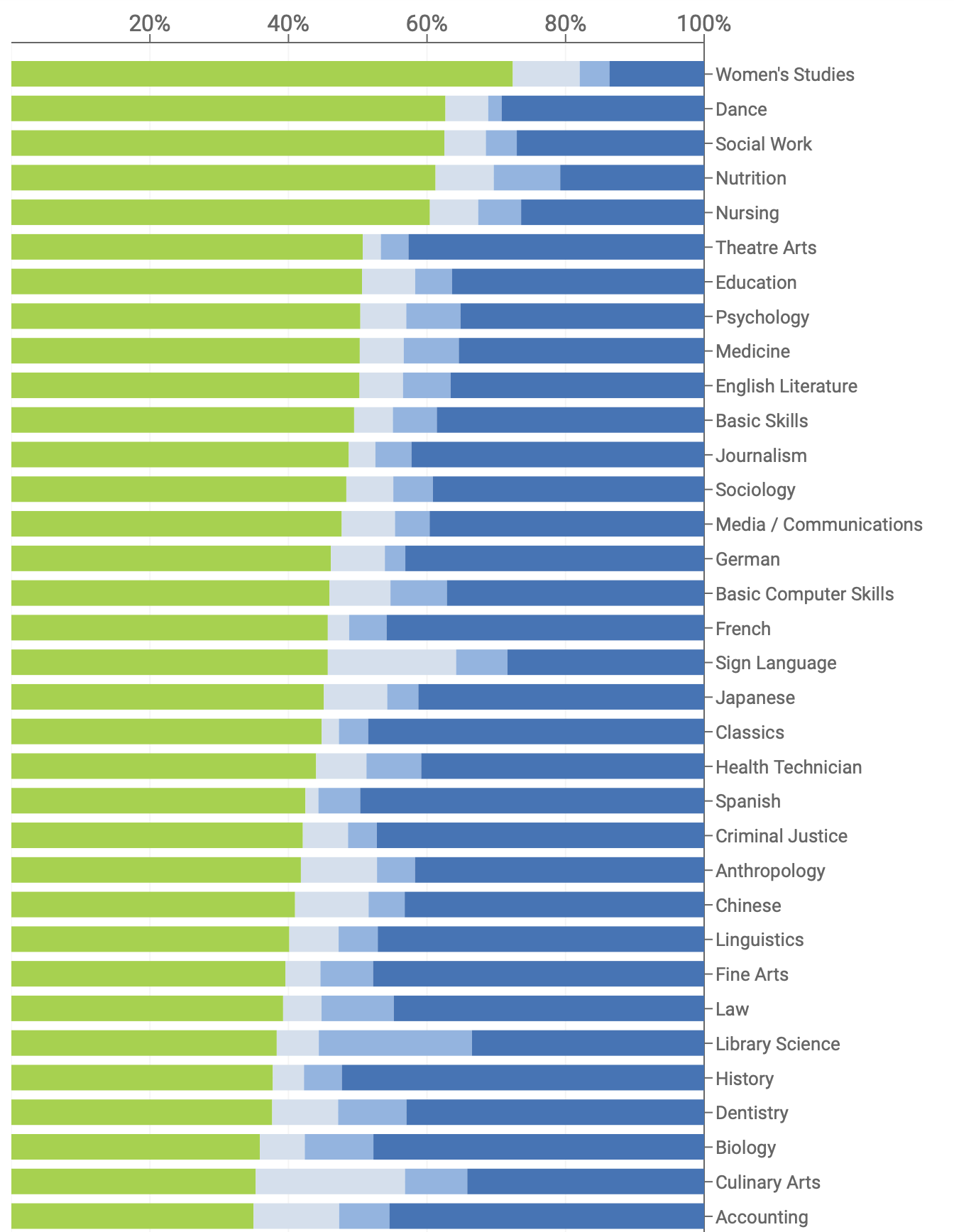

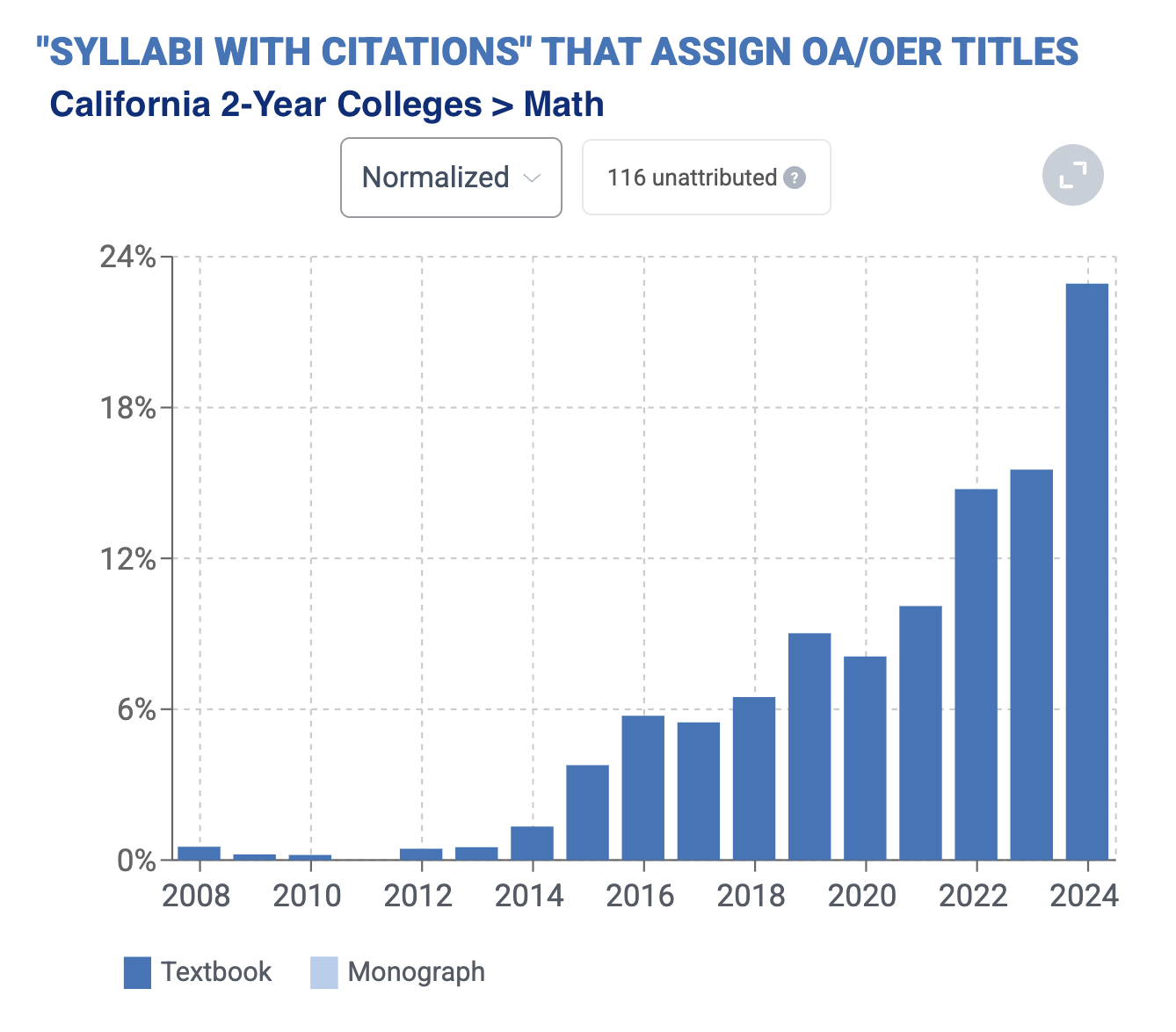

There are still major differences by field, reflecting the still-very-uneven availability of open titles in the gen ed curriculum. Math and Computer Science remain at the top of the list. At California two-year schools, over 20% of math courses use open titles.

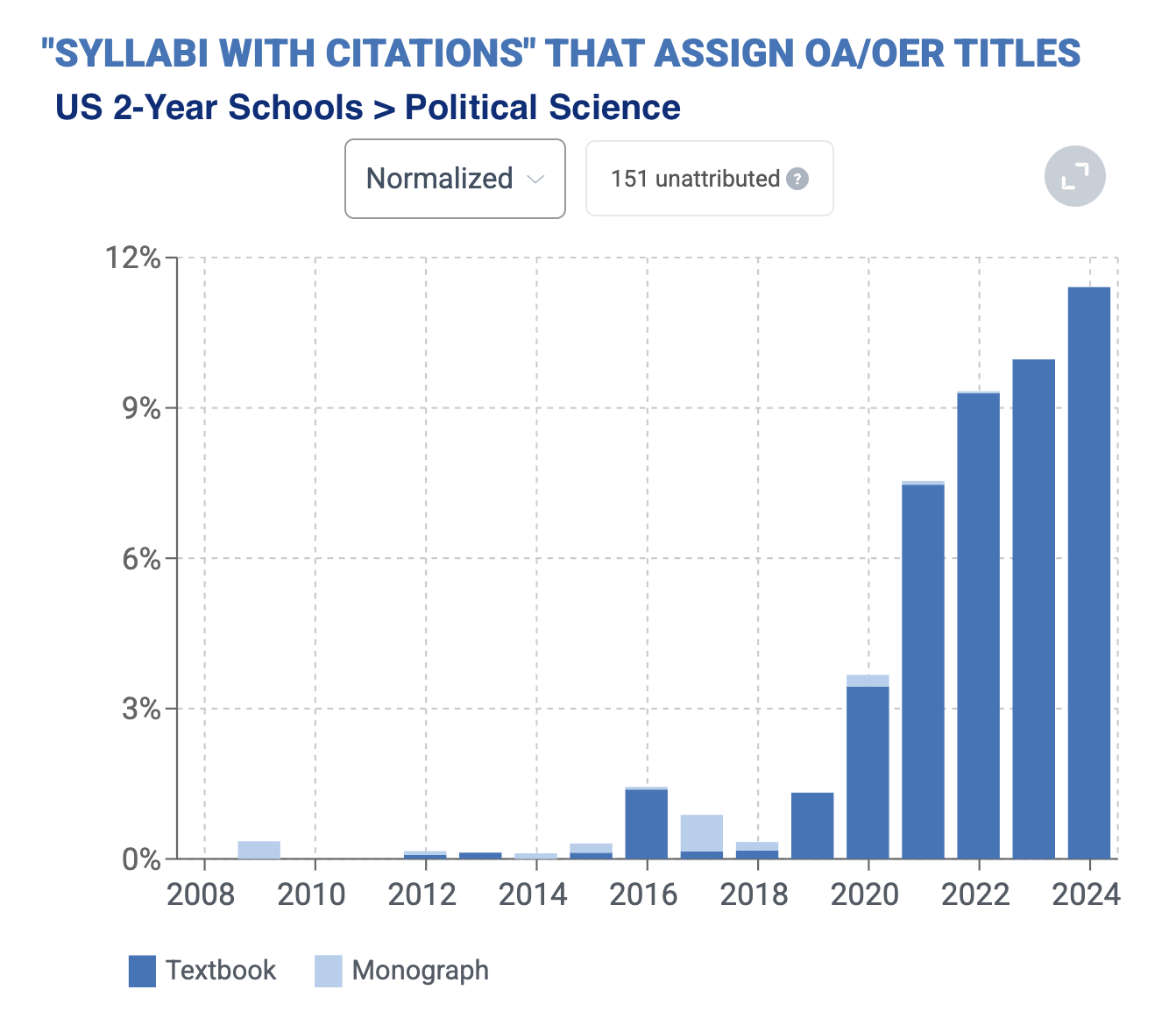

Take off can be rapid when a title successfully breaks into a major gen ed category, such as American Government survey classes. Glenn Krutz’ American Government textbook (2021) is responsible for almost all of the growth below — and in fact is higher than the chart indicates because syllabi routinely misspell his name as Kurtz, which leads to a citation undercount.

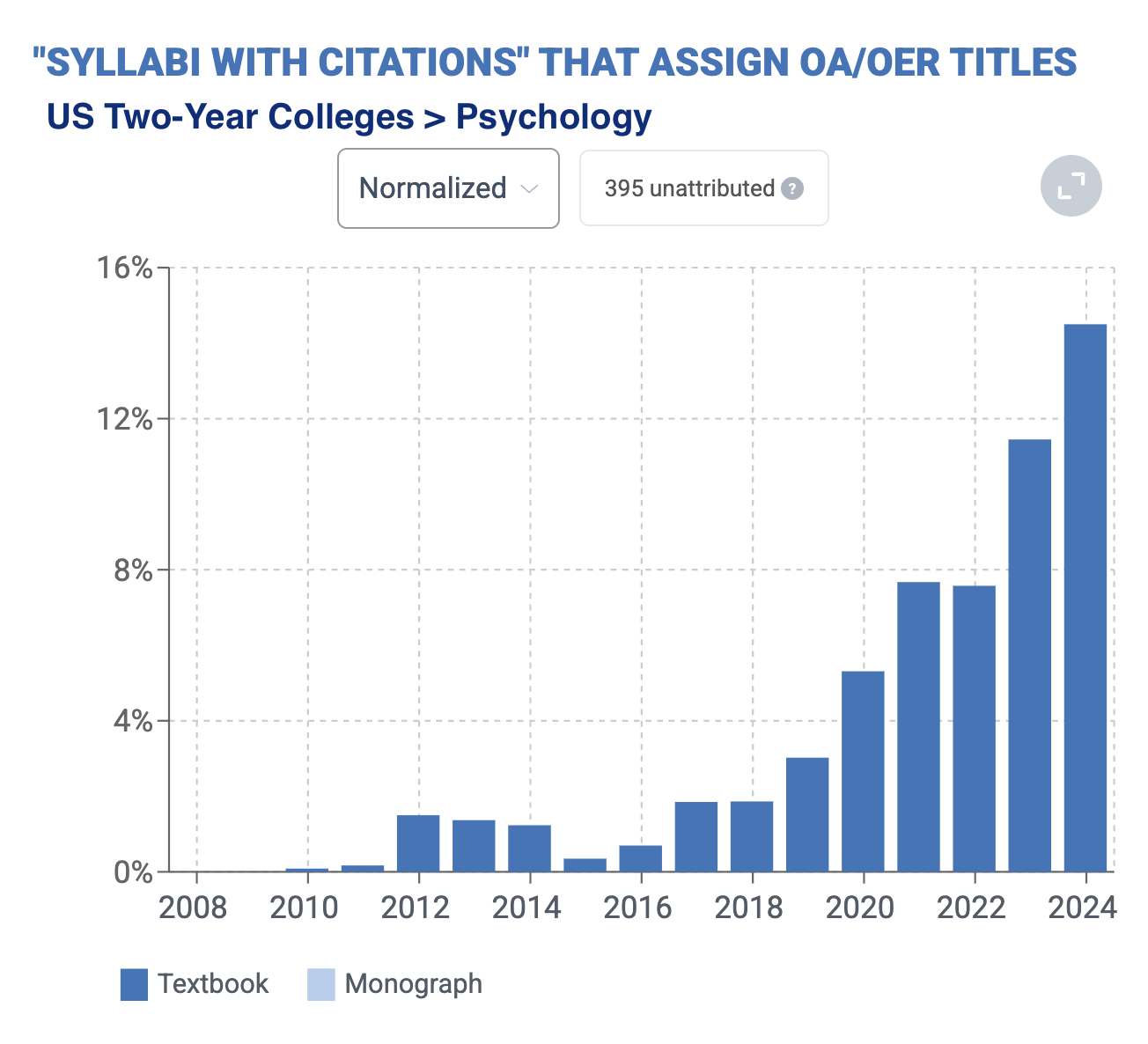

Much the same is true in Psychology, where Spielman’s Psychology (2020) has broken into the Intro to Psychology text pool.

Other fields are comparatively underserved, with no breakthrough titles. History, Sociology, Business, and Engineering are examples.

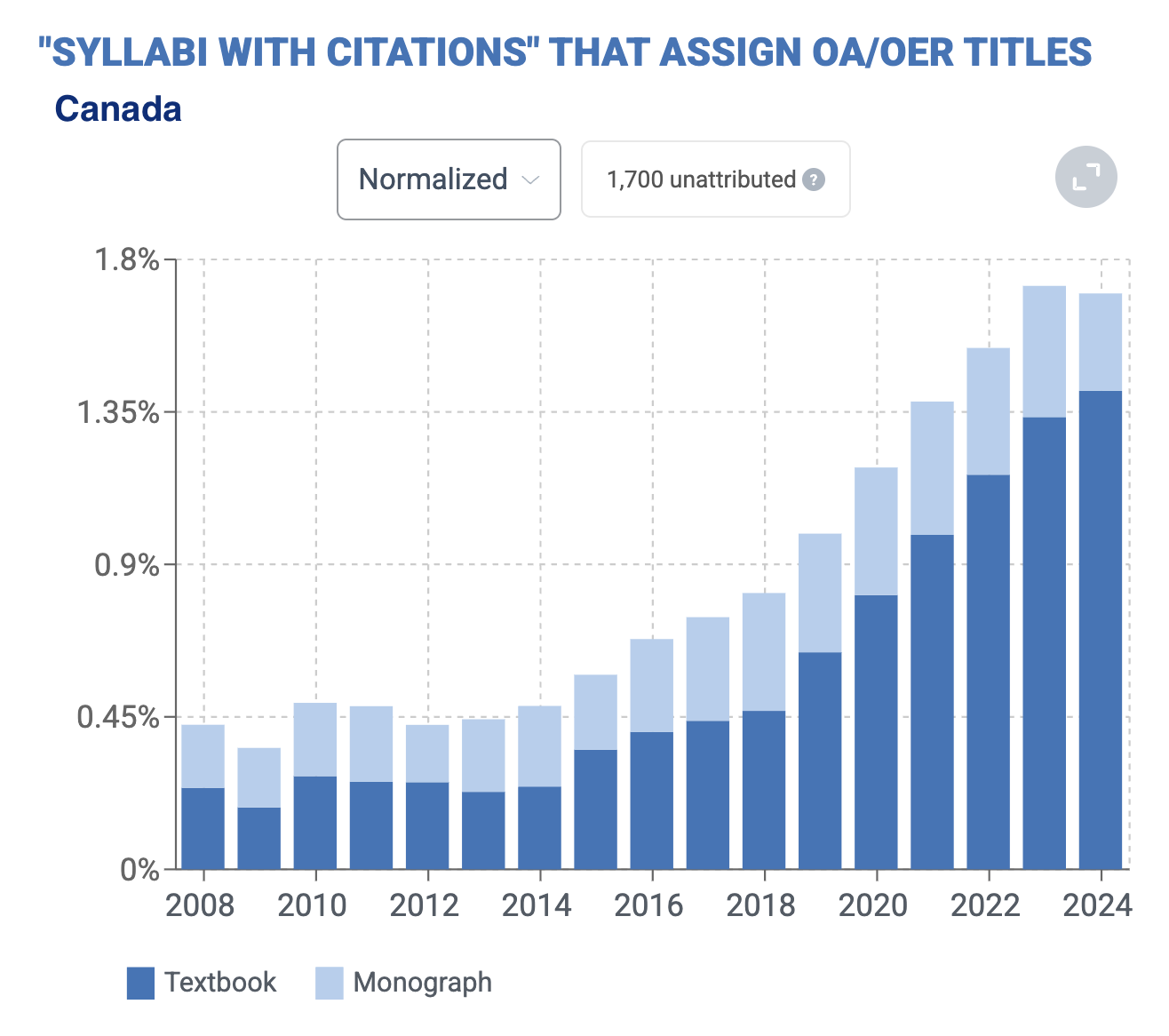

International data continues to show interesting variation. Canadian adoption patterns look a lot like the US, with a focus on introductory textbooks.

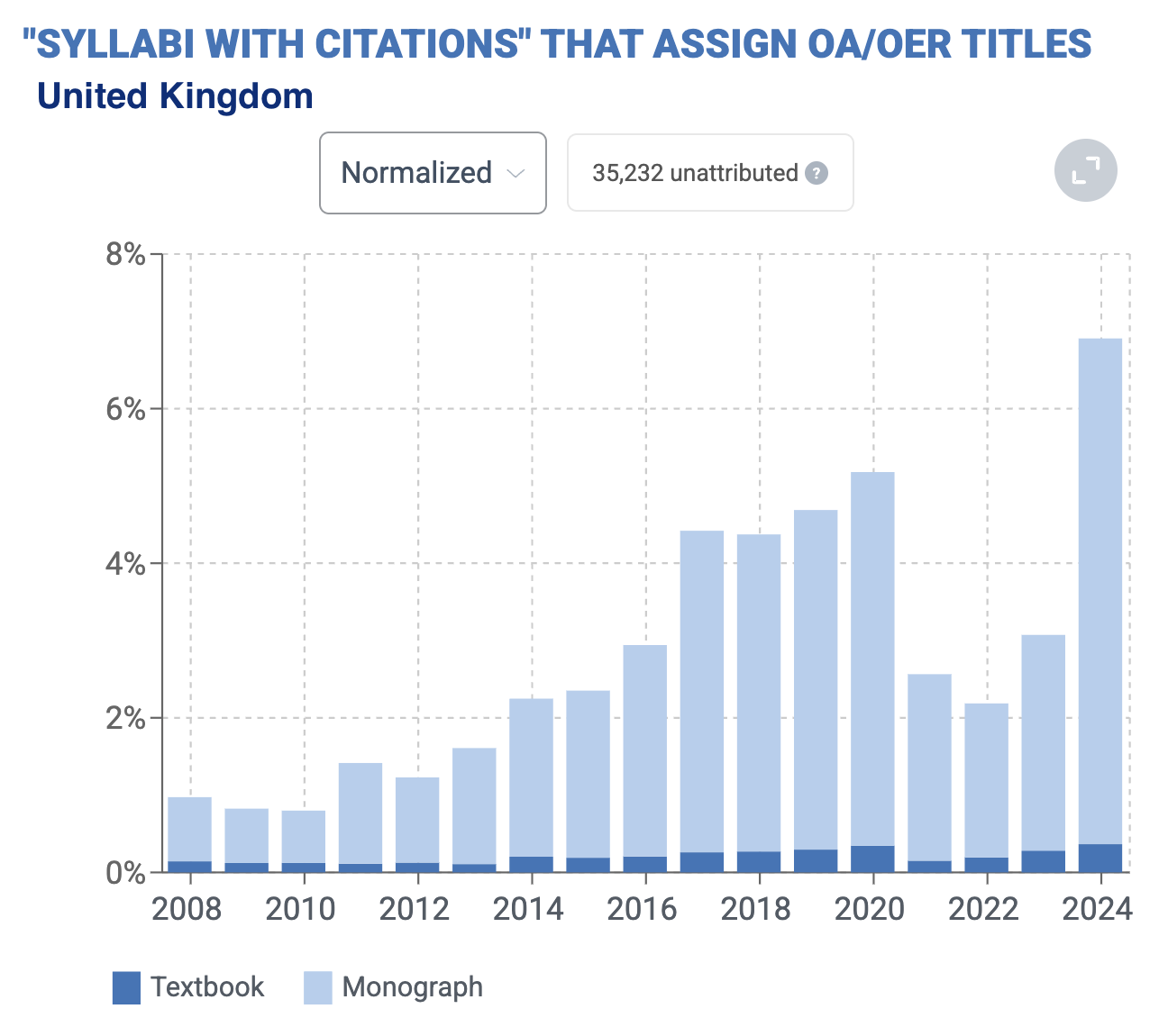

The UK, in contrast, has high levels of OA monograph adoption, but very low levels for textbooks. The ease of construction of secondary bibliographies in widely-used reading list tools like Talis and Leganto probably boosts the monograph numbers, but textbook adoption has clearly not been a focus.

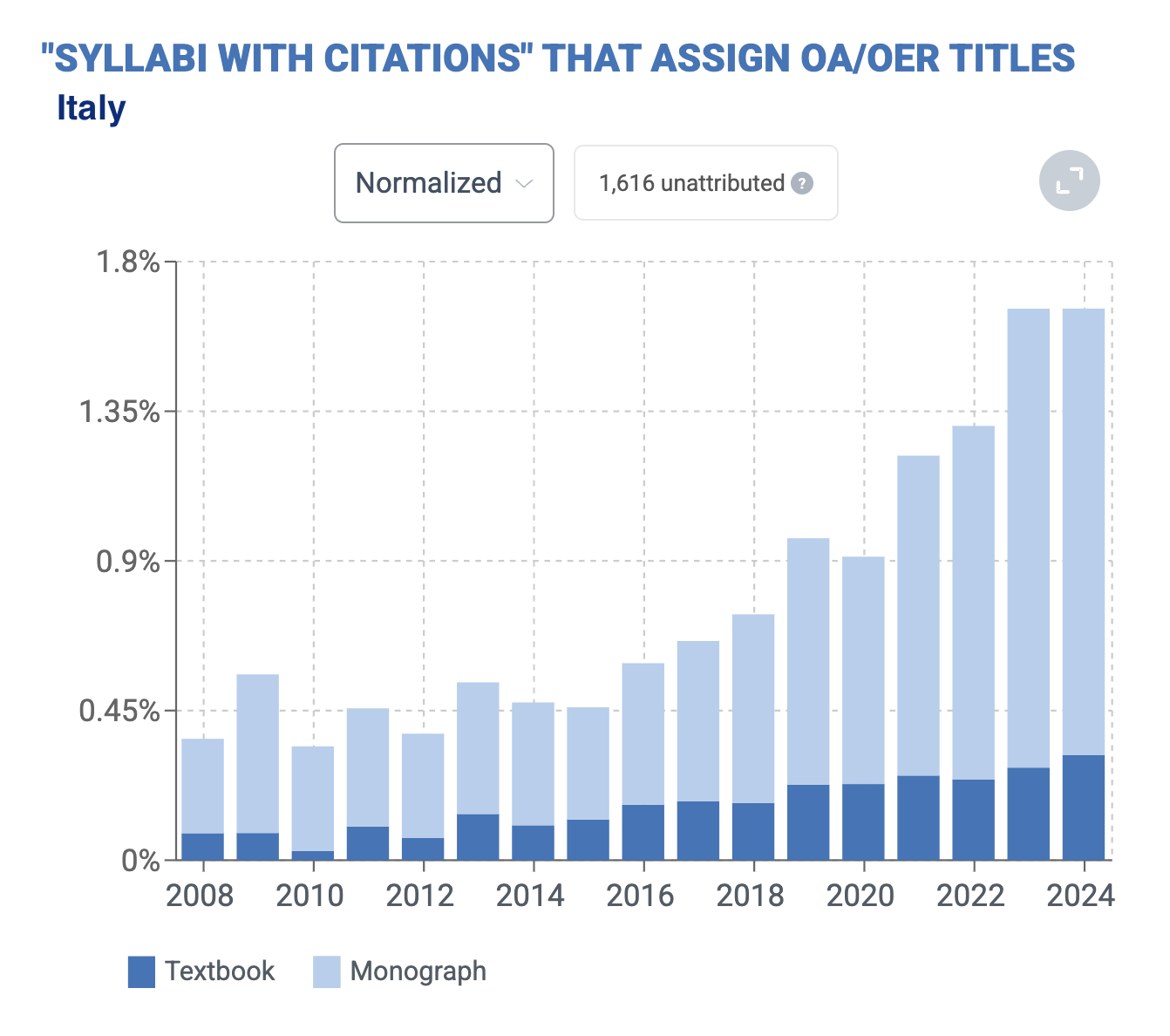

Other non-reading-list-using European countries show a similar pattern: heavy on monographs but light on textbooks. In earlier updates, we attributed this to the ease with which English-language research monographs circulate as optional reading through international research communities compared to the work of producing language-localized versions of open textbooks. This still seems plausible to us. Italy is typical in this regard..

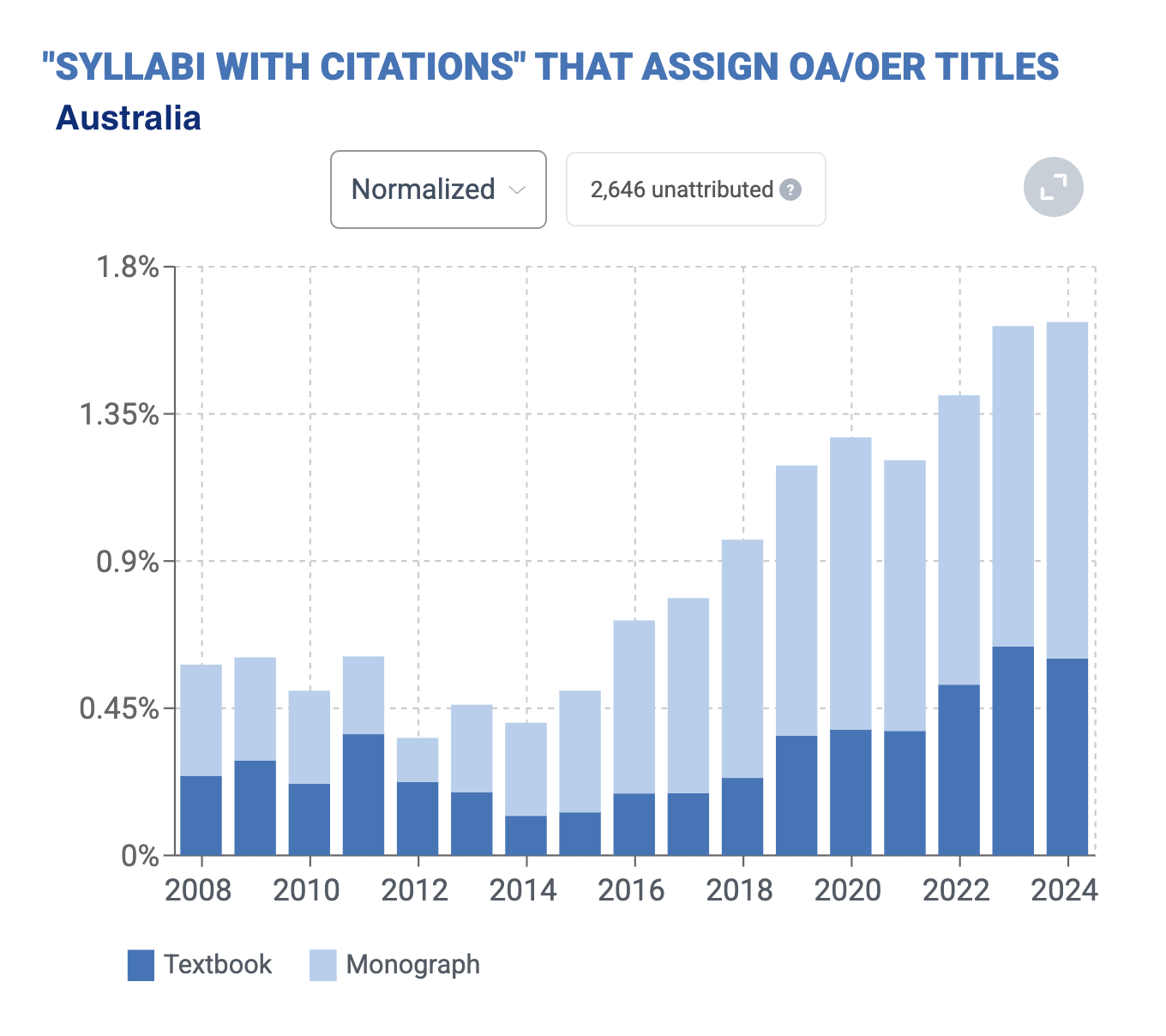

Australia falls between the two models.

As we put it last year:

The data outside the US and Canada point to differences between OER textbook publishing and 'OA' or open access scholarly monograph publishing, which remains the province of university presses. For OER textbook authors and publishers, the goal is to provide substitutes for commercial titles used in popular classes. An OER textbook can have a steep adoption curve because it has a large potential pool of classes to convert. This conversion process, in turn, has been formalized into policy and advocacy approaches, and has become an official responsibility of the library at many schools.

OA monographs, in contrast, come out of a more-or-less parallel but distinct movement to ensure that published research is free -- beginning with journal articles but extending to books and other research outputs. As research, OA monographs are usually specialized titles and almost by definition not intended to be direct substitutes for existing (commercial) titles.

The incentives and growth potential are accordingly different. Publishers are publishing more OA titles (measured by growth of the Directory of Open Access Books ), but they tend to fill small course niches and show up in classes that already assign a lot of other (commercial) books. The US and Canadian advocacy model doesn't apply as easily in this context, 'free' has less of an impact, and the textbook-based curriculum of two-year schools is largely irrelevant. This is, we think, the context for what we see in the US and Canadian data, which shows modest growth at best in the adoption of OA titles over the past ten years.

But elsewhere, the monograph vs textbook data is different and I don't think we have a complete explanation of it. One important factor is that the market-size dynamic is reversed: it's entry-level textbooks that are fragmented by country and language -- and dominated by translated commercial textbook titles -- while the research culture is international and built around English. English-language research monographs 'travel' better in this context and cost/benefit decisions shift accordingly.

We’ll refer back to last year’s update for a discussion of some of the caveats around the data — including the likelihood that OS undercounts OER adoptions, but probably not by a lot. You can learn more about OS's methods there too.