With the release of version 2.11 of the OS dataset, we can update our reporting on adoption rates for open educational resources (OERs) -- specifically, open textbooks and 'open access' monographs.

The defining thing about OERs is that they are released under an open license and so can be freely circulated and used. Because they are free, OERs have become an important part of efforts to lower the cost of higher education, which often includes thousands of dollars per student per year for course materials. But free comes with a small catch: because there is no sale or single distribution point, it's difficult to track the use of OERs. And this difficulty makes it hard to know whether adoption efforts are working. And this lack of feedback complicates decisions about whether and where and how to invest in the open ecosystem. The OER ecosystem is weaker, we would argue, because it's bad at closing this information loop between supply and demand.

And this is where Open Syllabus can play a role. We track OER adoption via the appearance of titles on syllabi -- the point of use rather than the point of sale or distribution. With nearly 21 million syllabi in the collection, we can provide accounts of adoption across individual schools, states, and countries, in and outside the US -- with some caveats that we'll get to below.

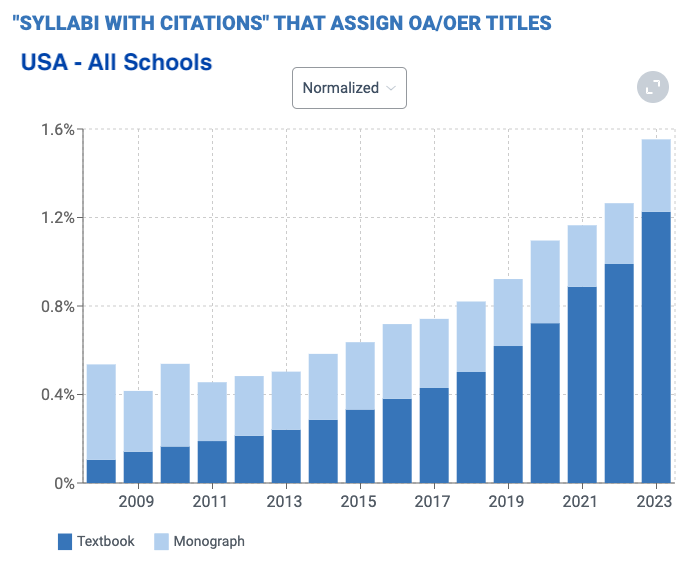

The new dataset adds two million syllabi and extends the timeline to 2023. Broadly, it expands on the story we've been telling for several years: rapid growth in OER textbook adoption in the US and Canada, but from a very low baseline in the mid 2010s, and rapid OER monograph adoption outside the US and Canada from similarly low baselines. What does this mean concretely?

In 2013, OER textbooks were barely on the scene in the US and used in only around 1 in 400 classes. By 2023, it was 1 in 80. Over the past 10 years, the growth rate in OER textbook use has averaged around 17.5% per year in the US.

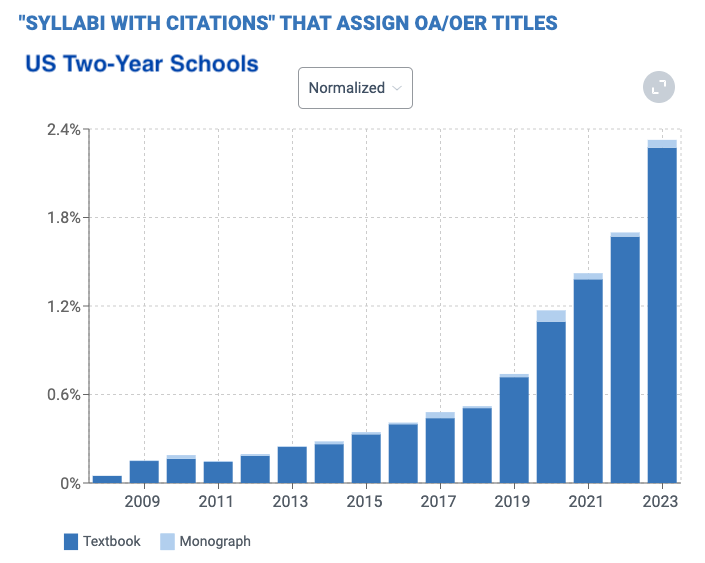

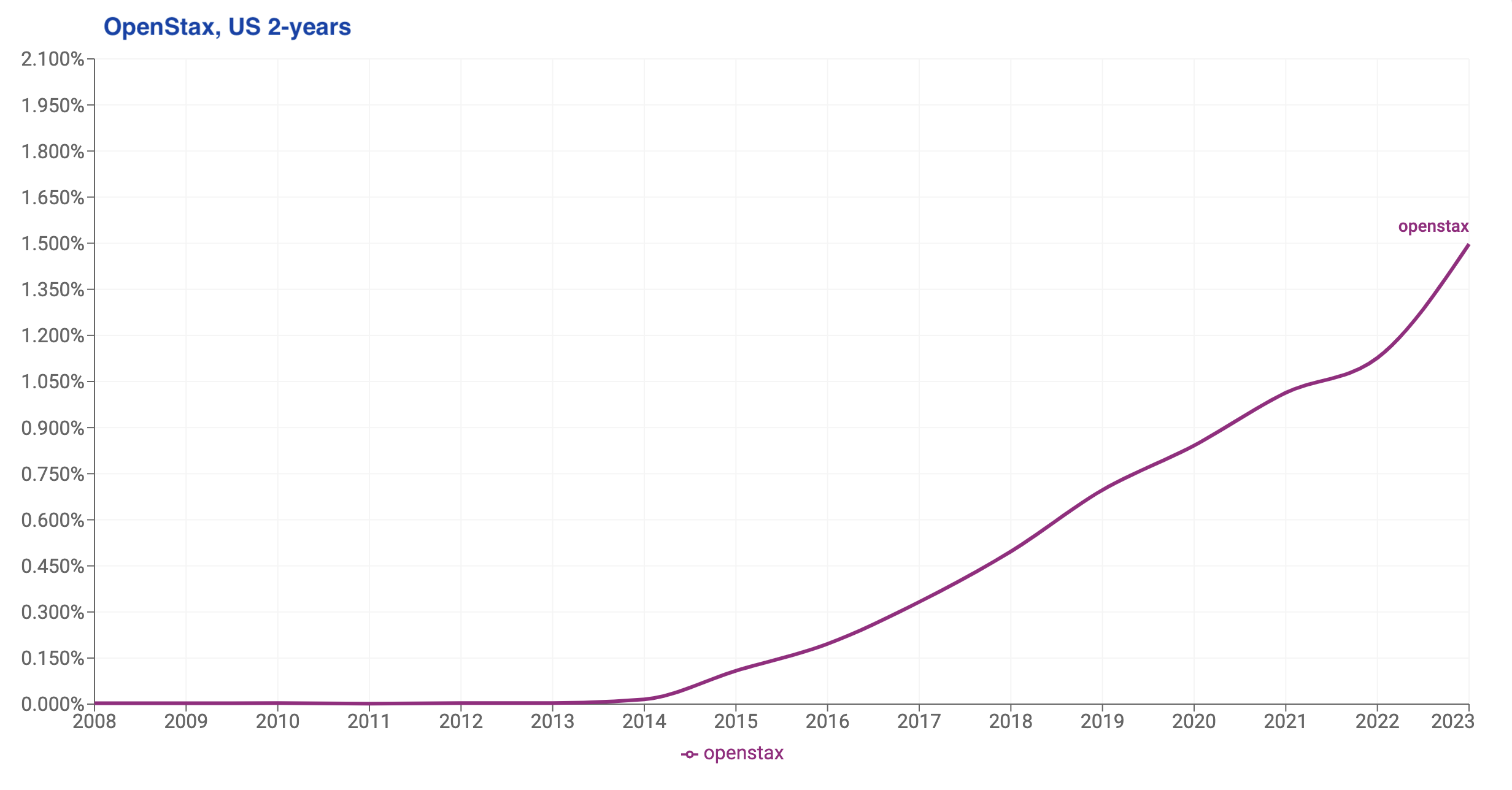

OER efforts have especially targeted two-year schools, where textbooks represent a larger portion of educational expenses and students are less able to afford them. This focus shows up clearly in the data. The adoption rate at two years is 1 in 40 classes -- with a growth rate of 26% per year over the past 5 years. Is this a tipping point? It's beginning to look like one.

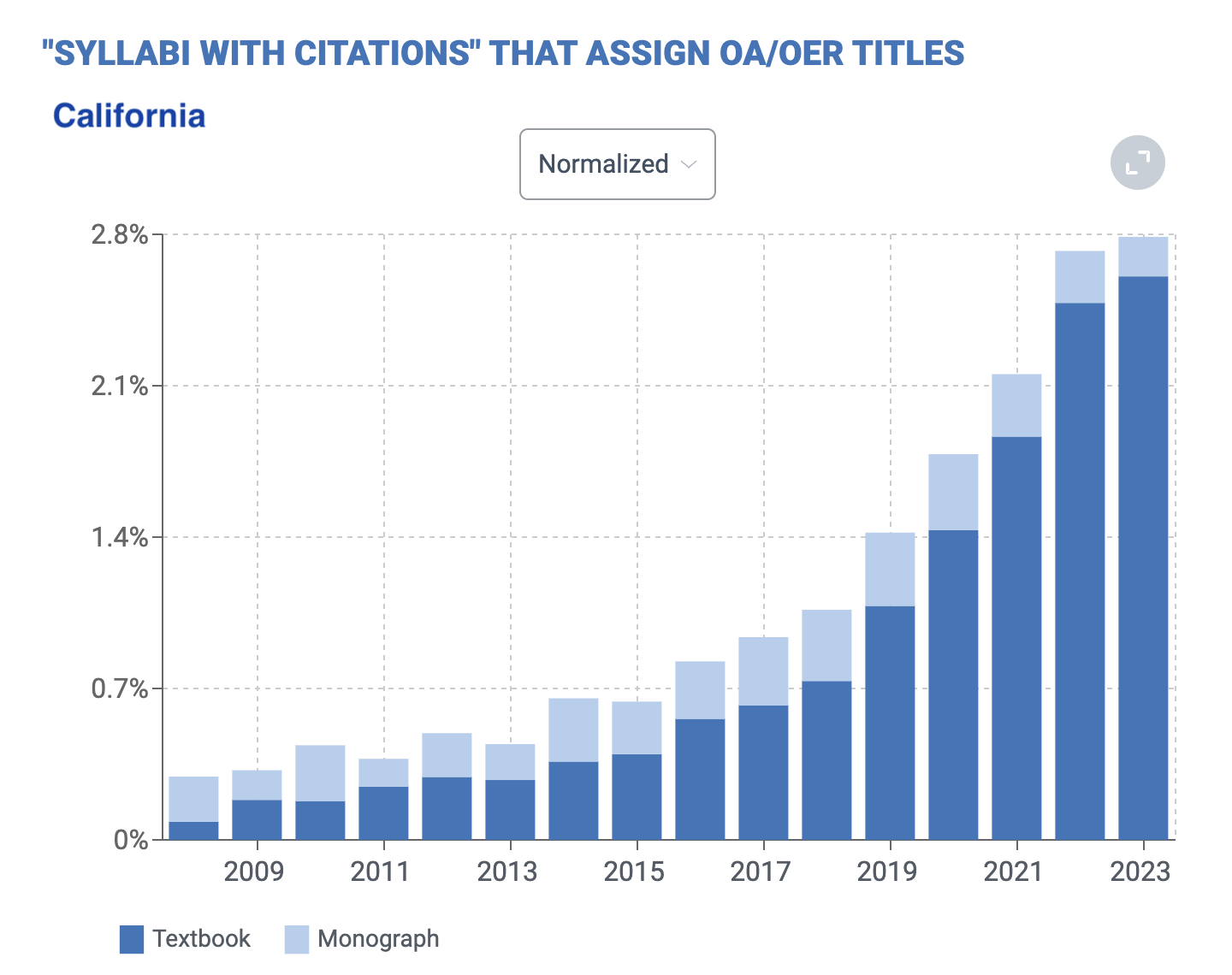

Because US higher ed is very decentralized, OER adoption in the US is shaped by state, system, and school-level policies. California, which has the best-supported state-level program, remains the national leader by a large margin: Over 1 in 40 classes use OER titles and 1 in 25 at two-year schools.

Among the other states for which we have decent data: Texas and Michigan are close to average. Georgia, Florida, Colorado, and Illinois fall below it.

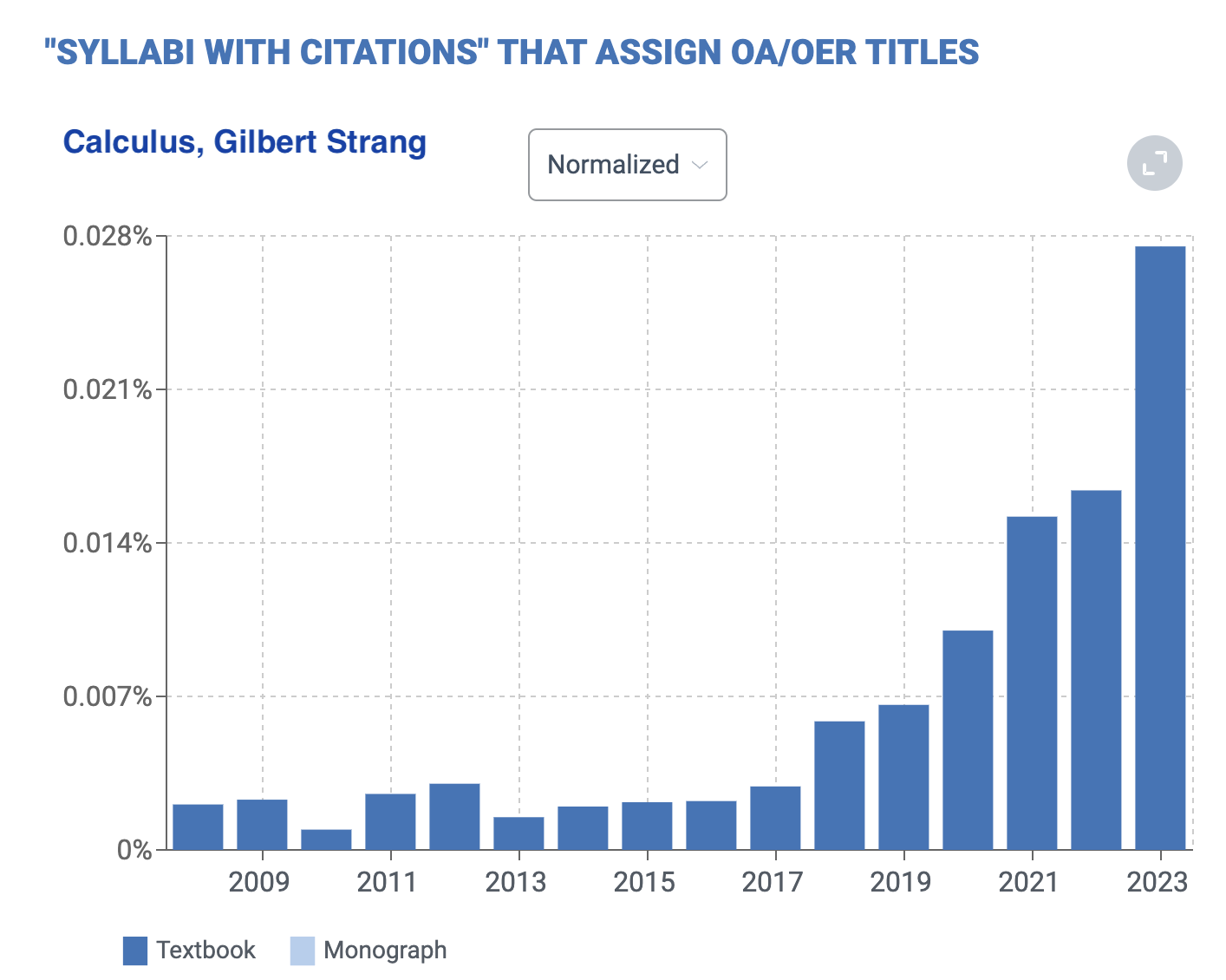

With respect to fields, math continues to be the leader, followed by computer science. 1 in 25 math classes use an OER textbook. Restrict to 2-years and it's 1 in 18.

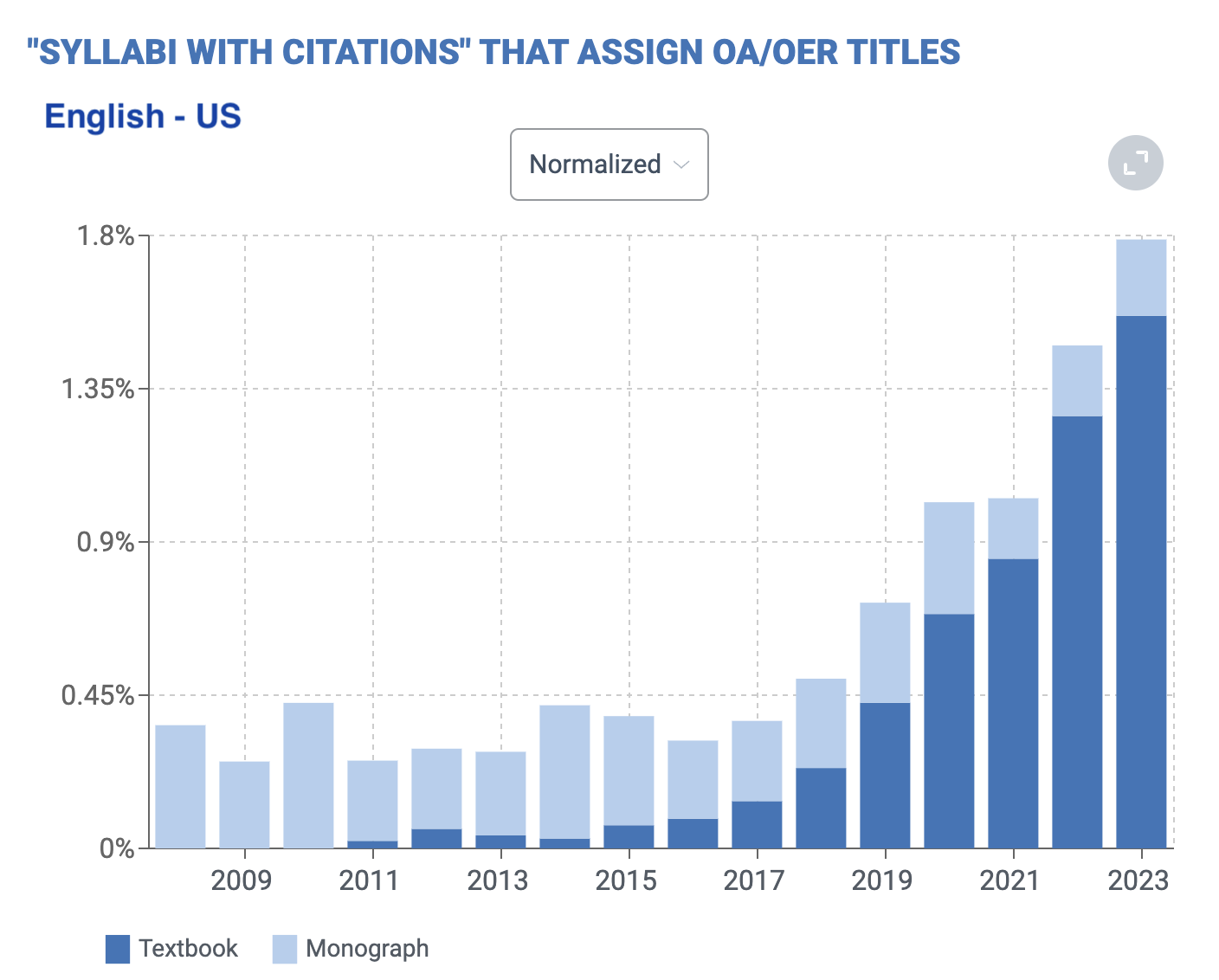

Other fields have begun to catch up as OER authors begin to fill some of the common entry-level class niches. Almost all of the growth in English and Education, for example, has happened since 2019 -- and in both cases due primarily to the emergence of writing guides and student success manuals. Methods books have gained traction across a number of social scientific and adjacent fields, including business. And recently developed, topic-specific textbooks for core classes in business, psychology, and political science have begun to gain traction.

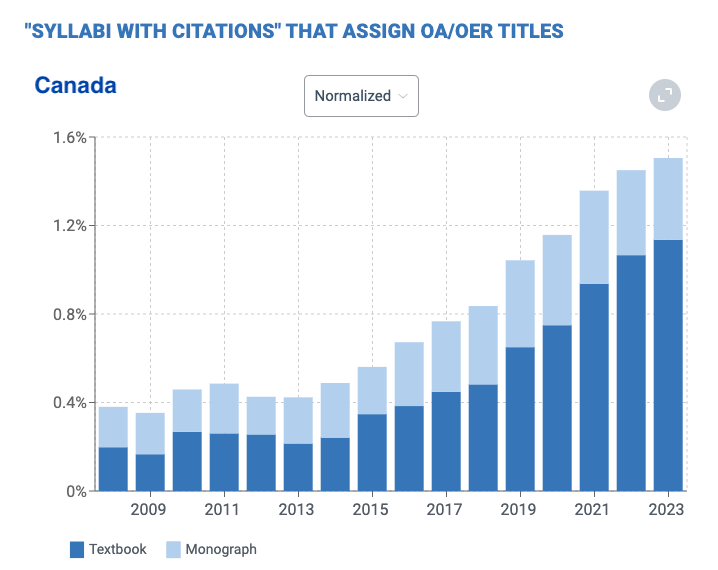

The open book ecosystem in other countries offers interesting points of comparison. Canadian OER adoption looks very similar to the US, both in terms of the rate of growth and the heavy focus on textbooks.

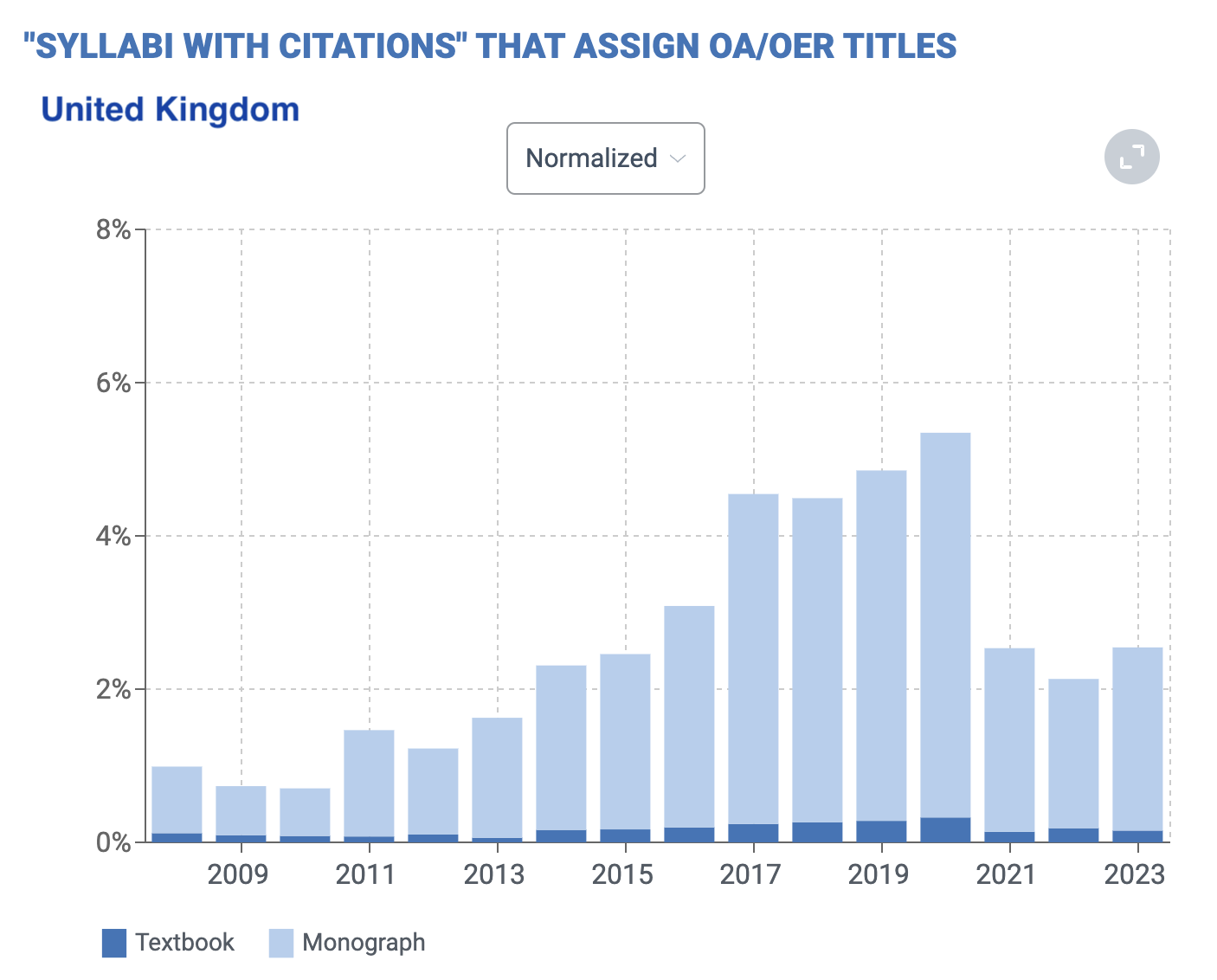

But adoption elsewhere is more heavily tilted toward monographs. Adoption in the UK is the extreme case, with rapid monograph growth and a very small role for textbooks.

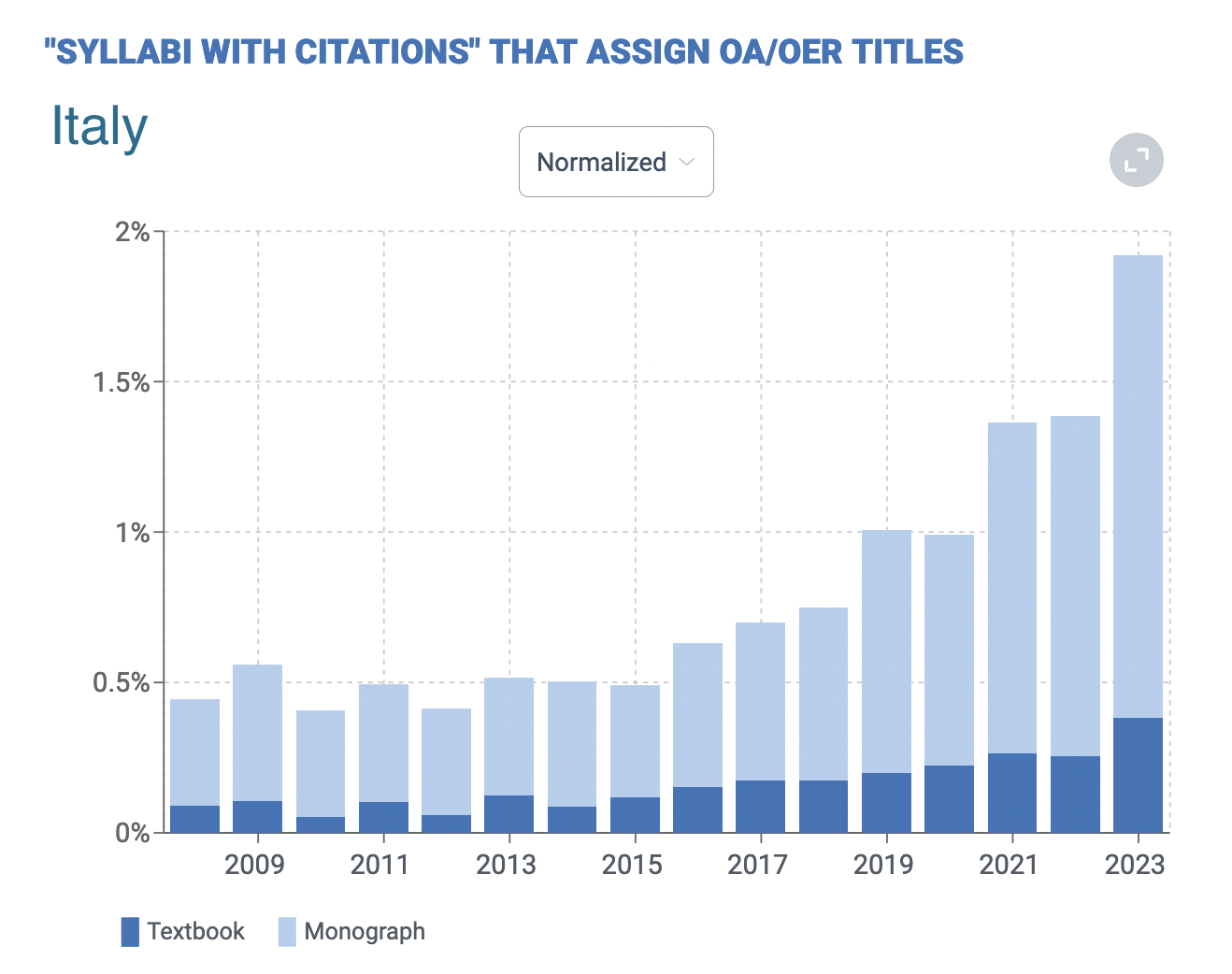

That downslope after 2020 reflects some data access problems related to a change in reading list software platforms in the UK (and Australia), so we are inclined to discount it. The more general pattern shows steady and in many cases very rapid monograph growth elsewhere in Europe where we have no such data problems. For example, Italy:

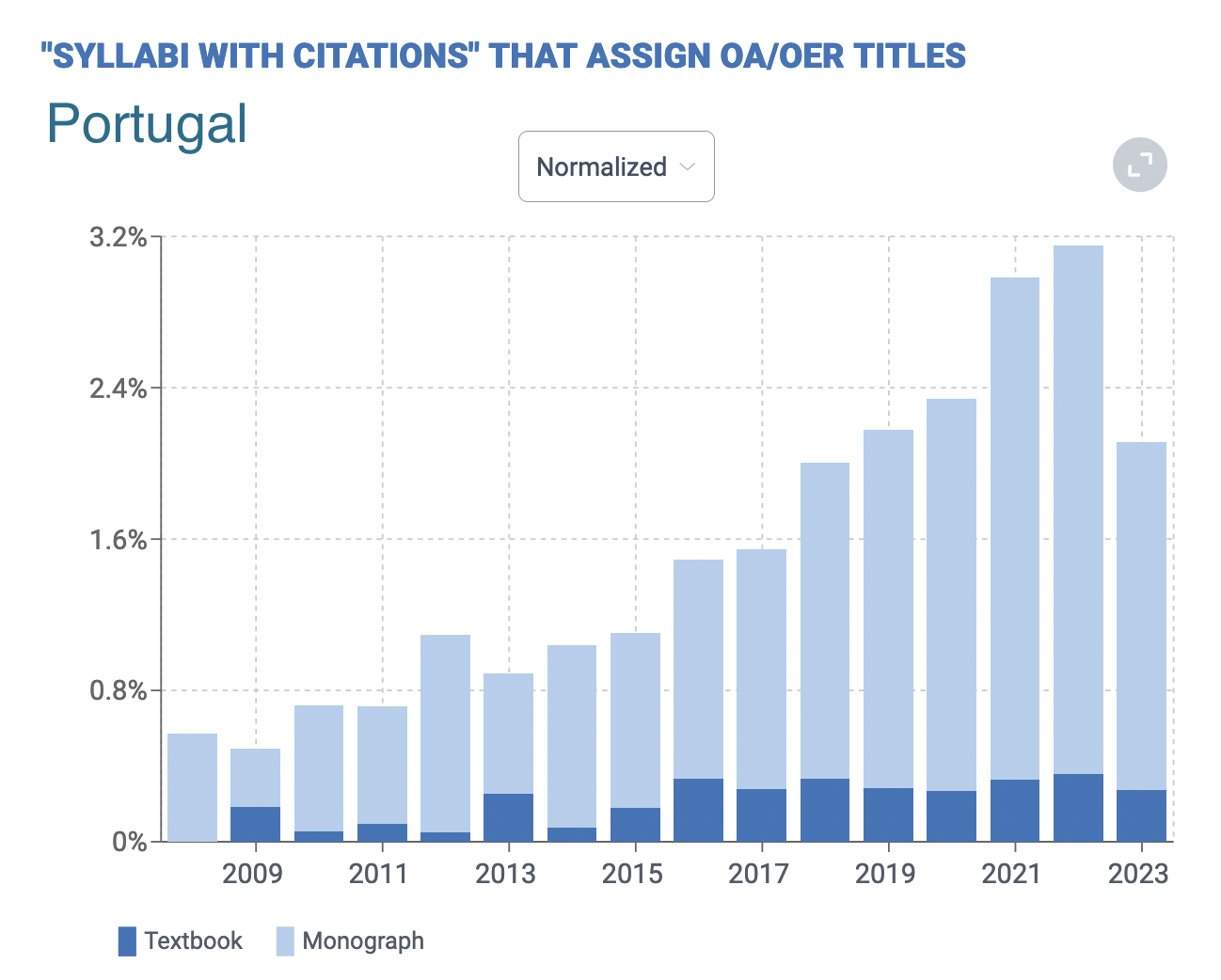

And Portugal:

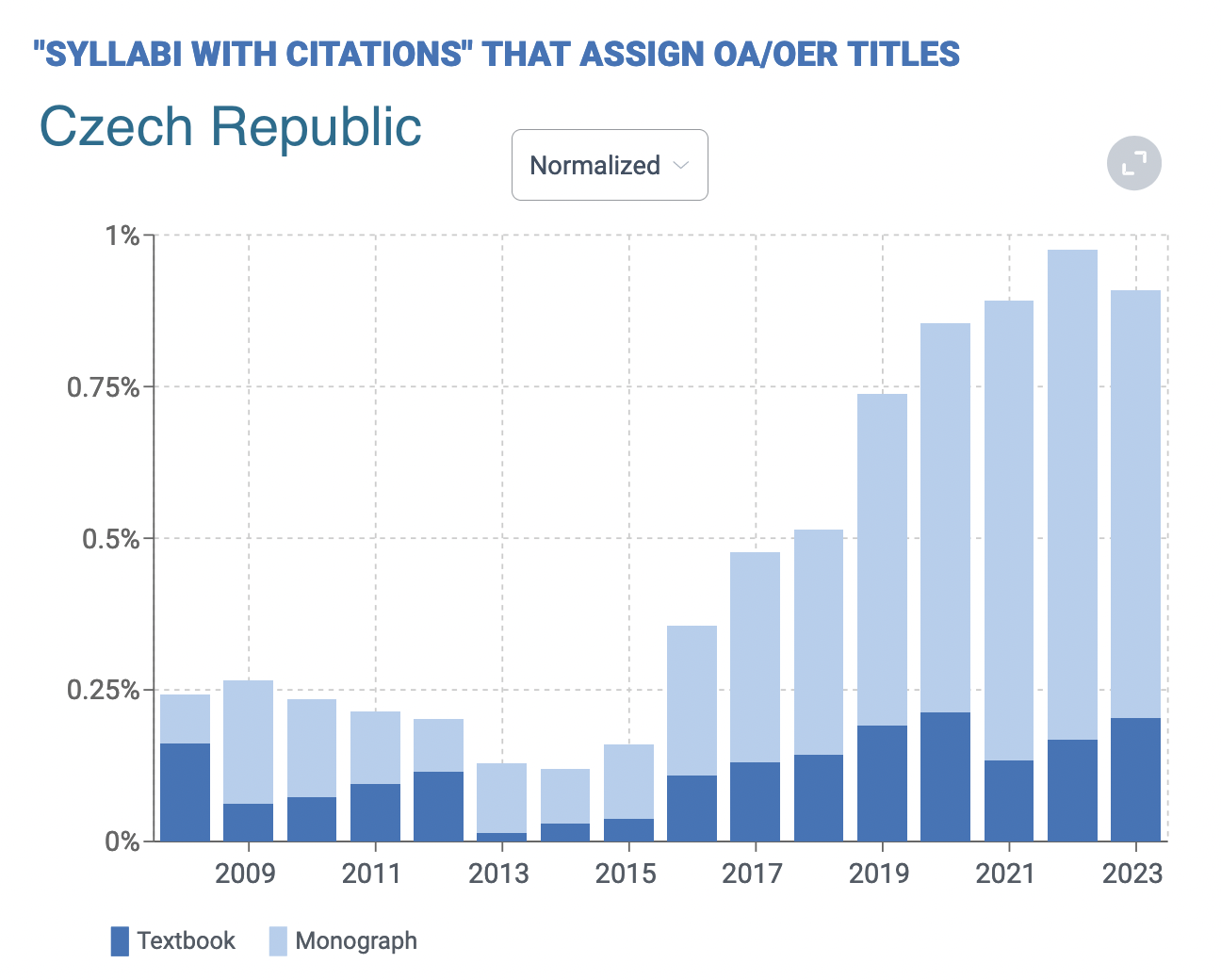

And the Czech Republic:

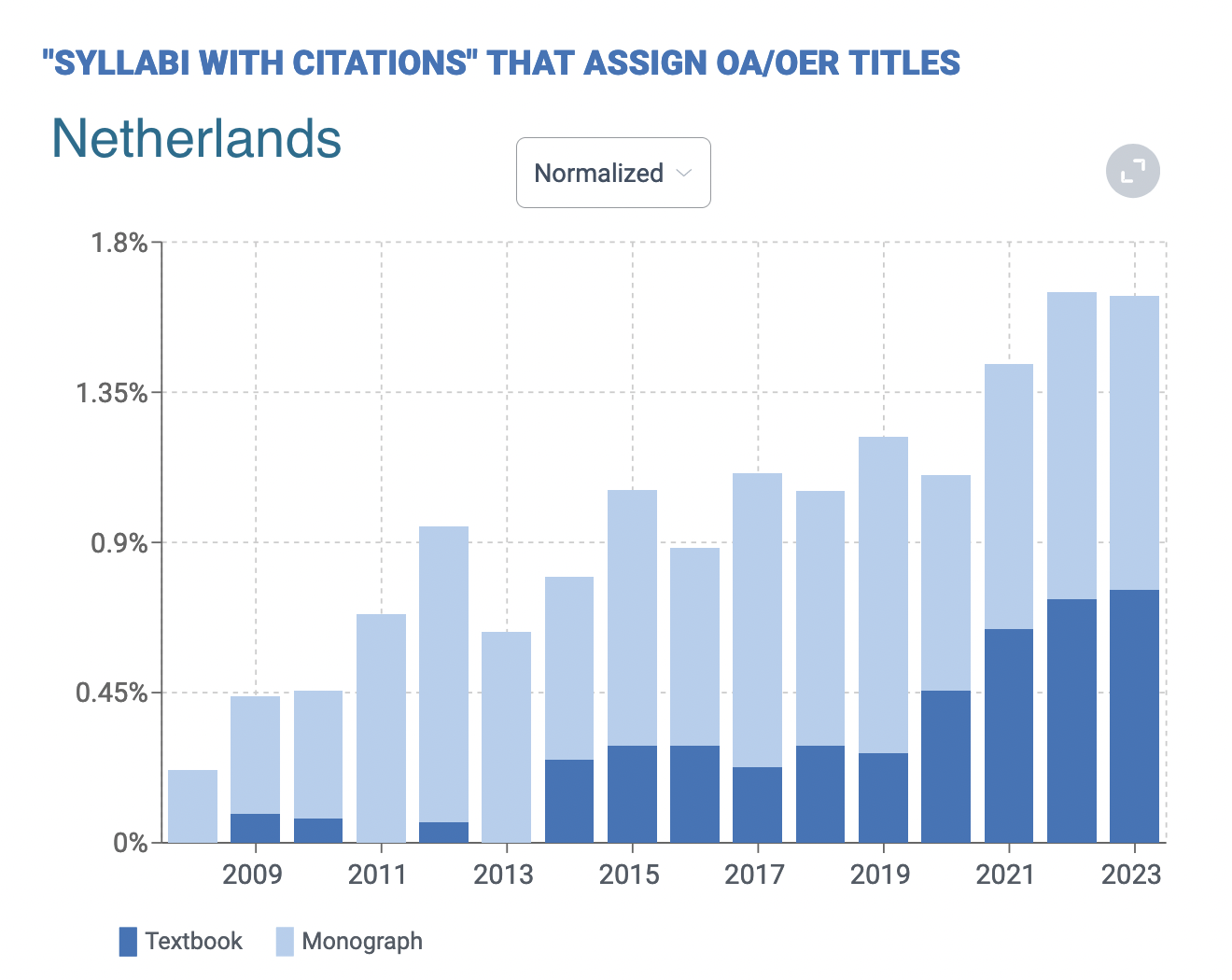

And to an extent in the Netherlands:

And also in Australia -- where overall adoption is lower but roughly evenly split between textbooks and monographs.

The data outside the US and Canada point to differences between OER textbook publishing and 'OA' or open access scholarly monograph publishing, which remains the province of university presses. For OER textbook authors and publishers, the goal is to provide substitutes for commercial titles used in popular classes. An OER textbook can have a steep adoption curve because it has a large potential pool of classes to convert. This conversion process, in turn, has been formalized into policy and advocacy approaches, and has become an official responsibility of the library at many schools.

OA monographs, in contrast, come out of a more-or-less parallel but distinct movement to ensure that published research is free -- beginning with journal articles but extending to books and other research outputs. As research, OA monographs are usually specialized titles and almost by definition not intended to be direct substitutes for existing (commercial) titles.

The incentives and growth potential are accordingly different. Publishers are publishing more OA titles (measured by growth of the Directory of Open Access Books ), but they tend to fill small course niches and show up in classes that already assign a lot of other (commercial) books. The US and Canadian advocacy model doesn't apply as easily in this context, 'free' has less of an impact, and the textbook-based curriculum of two-year schools is largely irrelevant. This is, we think, the context for what we see in the US and Canadian data, which shows modest growth at best in the adoption of OA titles over the past ten years.

But elsewhere, the monograph vs textbook data is different and I don't think we have a complete explanation of it. One important factor is that the market-size dynamic is reversed: it's entry-level textbooks that are fragmented by country and language -- and dominated by translated commercial textbook titles -- while the research culture is international and built around English. English-language research monographs 'travel' better in this context and cost/benefit decisions shift accordingly. There are also differences in the publishing and advocacy cultures that have grown up around Open Access research initiatives, with more active roles for libraries in funding new work. We'll just note this for now without venturing a full explanation.

We've alluded to a few caveats on the data already, and such a discussion could go on for some time. But let's address one that matters to the OER community.

There is reason to think that we undercount OER adoption -- though not dramatically with respect to anglophone countries. One source of undercount is our incomplete catalog of open titles. For the current dataset, we combine The Directory of Open Access books (for monographs), the Open Textbook Library (for textbooks), and parts of Academic Commons. (We also filter out public domain titles, which have begun to creep into OA/OER catalogs in new editions or translations). This the 'high end' of OER production in English -- most of it passing through peer review and/or press development processes. But these sources will miss a lot of non-English material relevant in other countries as well as less-formally-published work, such as material produced and circulated for departmental use or variations and remixes that are never recatalogued, and so on. There are archives for these materials but every new source that we integrate produces trade-offs between signal and noise in the data, so we move forward with caution.

A related source of undercount is the set of citation shortcuts that have grown up around some categories of OER title, including especially the replacement of authors by publishers in citations on syllabi. A typical example might list 'Chemistry by OpenStax' on a syllabus rather than Chemistry by some representation of the actual contributing editors and authors, which is our usual requirement for identifying titles. We can do a sanity check on this 'missing' material to some extent by searching our collection for the term OpenStax. It appears on 1 in 125 US syllabi and 1 in 65 at 2-year schools -- ballpark consistent, we would argue, with our updated approach to these citations. But there are certainly other scenarios and cases that we miss. These issues also affect all OA/OER cataloguing efforts -- and we inherit the problems of the catalogs we use.

Loosening concepts of authorship are a challenge for our work but also, arguably, for a community that treats attribution as a primary reward for OER publishing. This is an inherent tension in the OER community, which also values the right to remix open content. For our part, we think that we get the trend lines generally correct and undershoot a bit on the magnitudes.

The trend lines describe not just instances of adoption but also underlying processes of adoption that have institutional momentum -- and that momentum matters a great deal. Textbook choice, especially, is sticky -- costly to change -- and it can take a long time for new titles to take off. The major OER math titles are over a decade old. The computer science titles a bit older. Social science titles and business titles have begun to emerge in significant numbers only in the last five years. And this isn't long in curricular terms. Major commercial textbooks are often decades-old brands that become synonymous with their teaching subjects.

Last year, we asked whether the growth rate for OER titles will be sustained. This year's data provides a provisional yes. We'll continue to chart that progress and if we’re right, by charting it, accelerate it.

(April 18: updated with more thinking about the monograph data)