Much of the attention to ‘woke’ politics in higher ed assumes that the curriculum is a major driver of it – that students learn new ways of thinking about race or gender or inequality from their classes. This is a topic where the analysis of millions of syllabi can perhaps shed some light. At the risk of saying something both obvious and controversial, the curriculum of US higher education is very 'small c' conservative, built around long-term, slow-changing approaches to skills and knowledge in different fields. Our data suggests that it is, over the short and medium term at least, pretty insensitive to political and cultural change, and even to major shifts in knowledge and technology. This varies somewhat by field, of course, but not by that much.

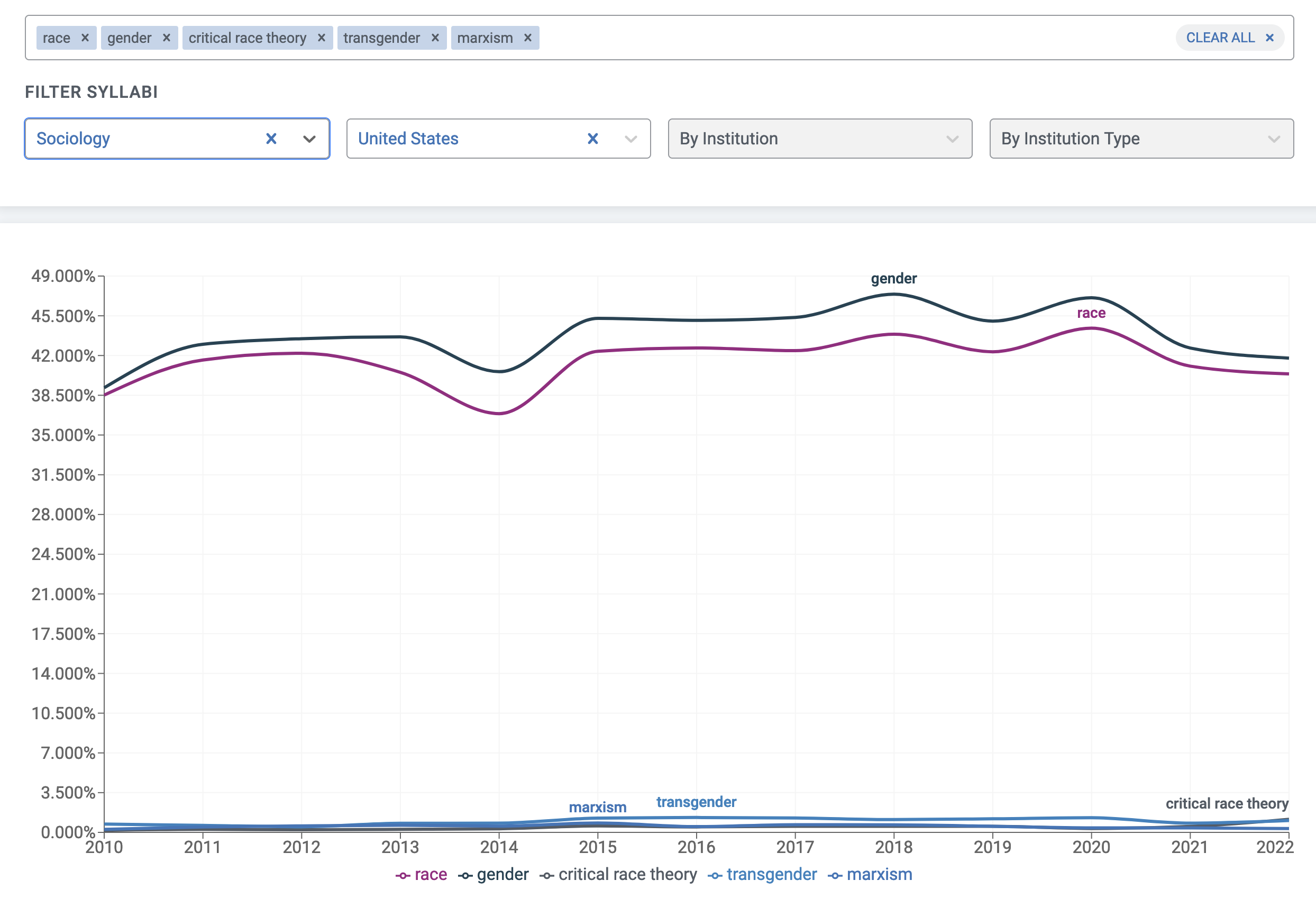

We can test this claim in limited ways with the 'Trends' dashboard in OS Analytics, which permits keyword and phrase searches across the descriptive content of 18.7 million syllabi. What jumps out? Well – restricting the search to US syllabi – few classes deal with the main topics of ‘woke’ politics at all. Under 5% of classes reference "gender." 3% reference "race." Zoom in on some of the more contested vocabulary around these topics and mentions become very scarce. "Marxism," "transgender," and "critical race theory" each figure in around .1% of classes -- 1 in 1000 classes.

Limit the range to R1 and R2 (research) universities and the percentages increase to around.... .2%.

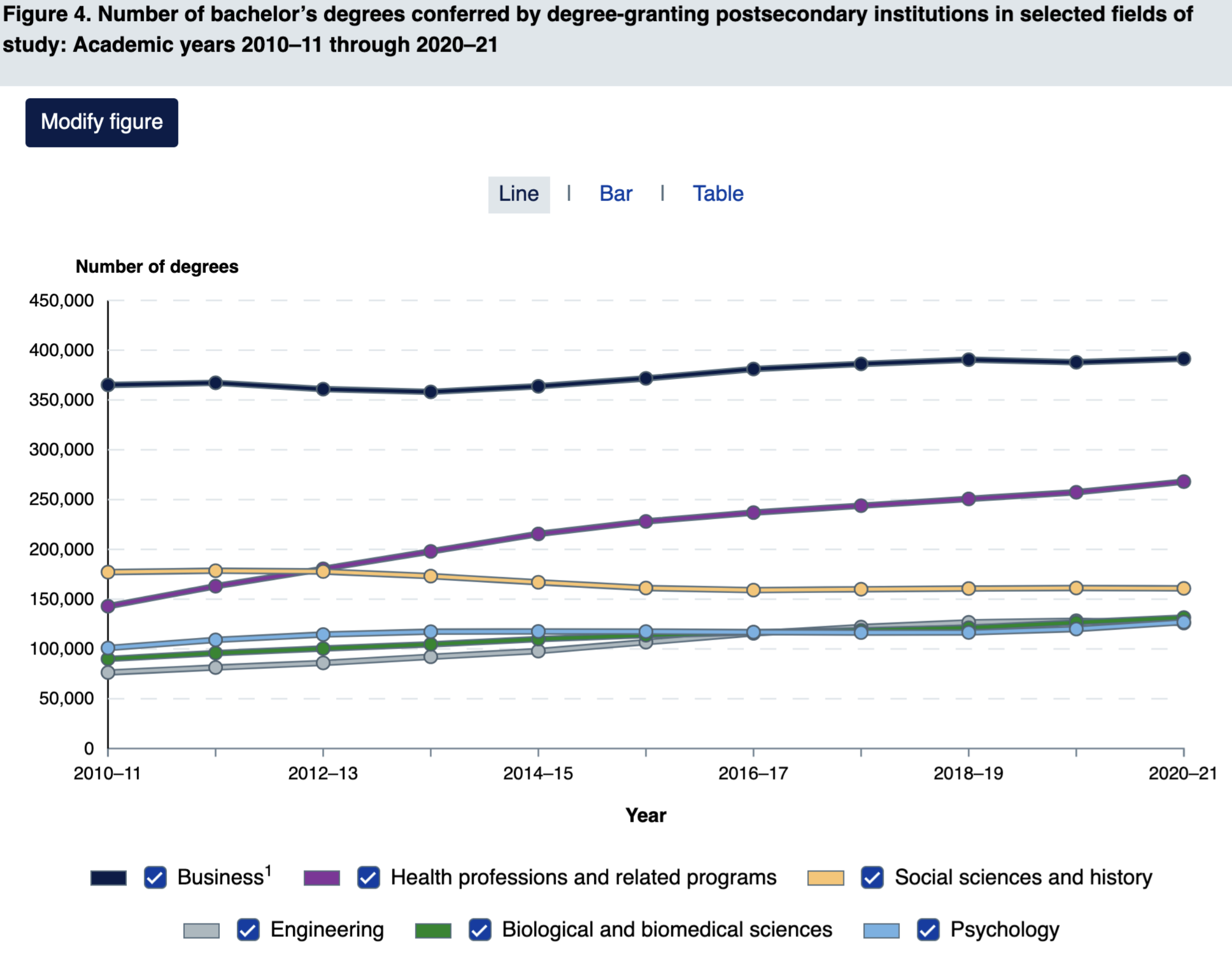

The simple explanation for this is that there are lots of fields that only rarely engage with these issues. You can get through a STEM, health, or business degree, and even some social science degrees without encountering them in significant ways in class. And those are the degrees that most students get. Around 1 in 6 students graduates with a business degree and another 1 in 6 with a degree in a health field. Around 1 in 500 students graduates with a degree in what the Dept of Ed lumps together as "Area, Ethnic, Cultural, Gender, and Group Studies." From the National Center for Educational Statistics:

There are, of course, larger fields in which race and gender are central subjects: sociology, for example, which accounts for roughly 1 in 125 graduates. Each of the two terms figures in around 40% of sociology syllabi. But marxism, transgender, and CRT? Barely 1%.

Here's Political Science, where marxism has an obvious role to play. It's around 1%.

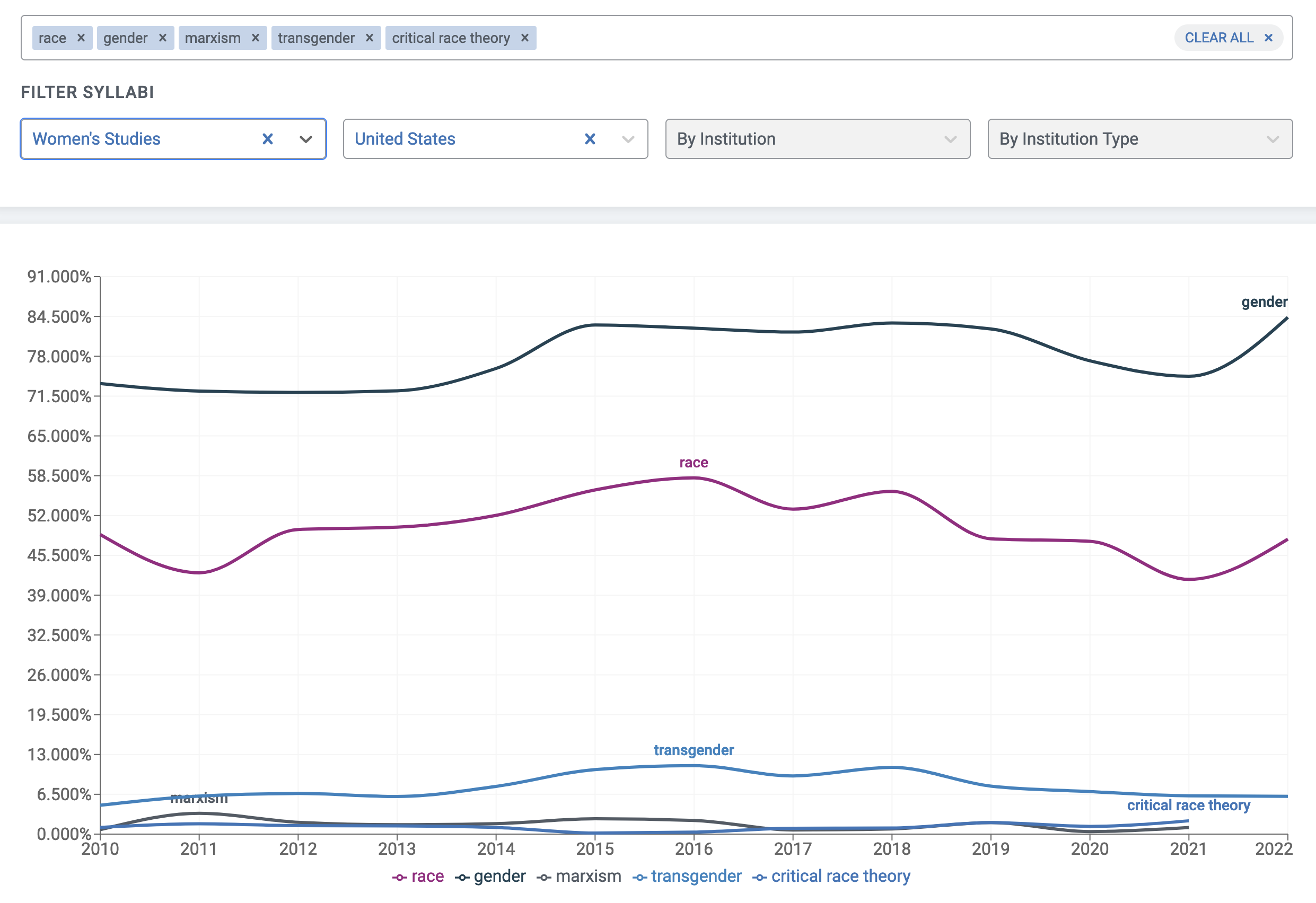

What about Women's Studies? Here's a good sanity check on our data, since one would expect gender to figure very prominently. And yes it does, generally north of 80% of syllabi. ‘Transgender,’ on the other hand, hovers somewhere above 6% in recent years. Here, as elsewhere, the stability is striking. None of these terms has moved much in the past decade.

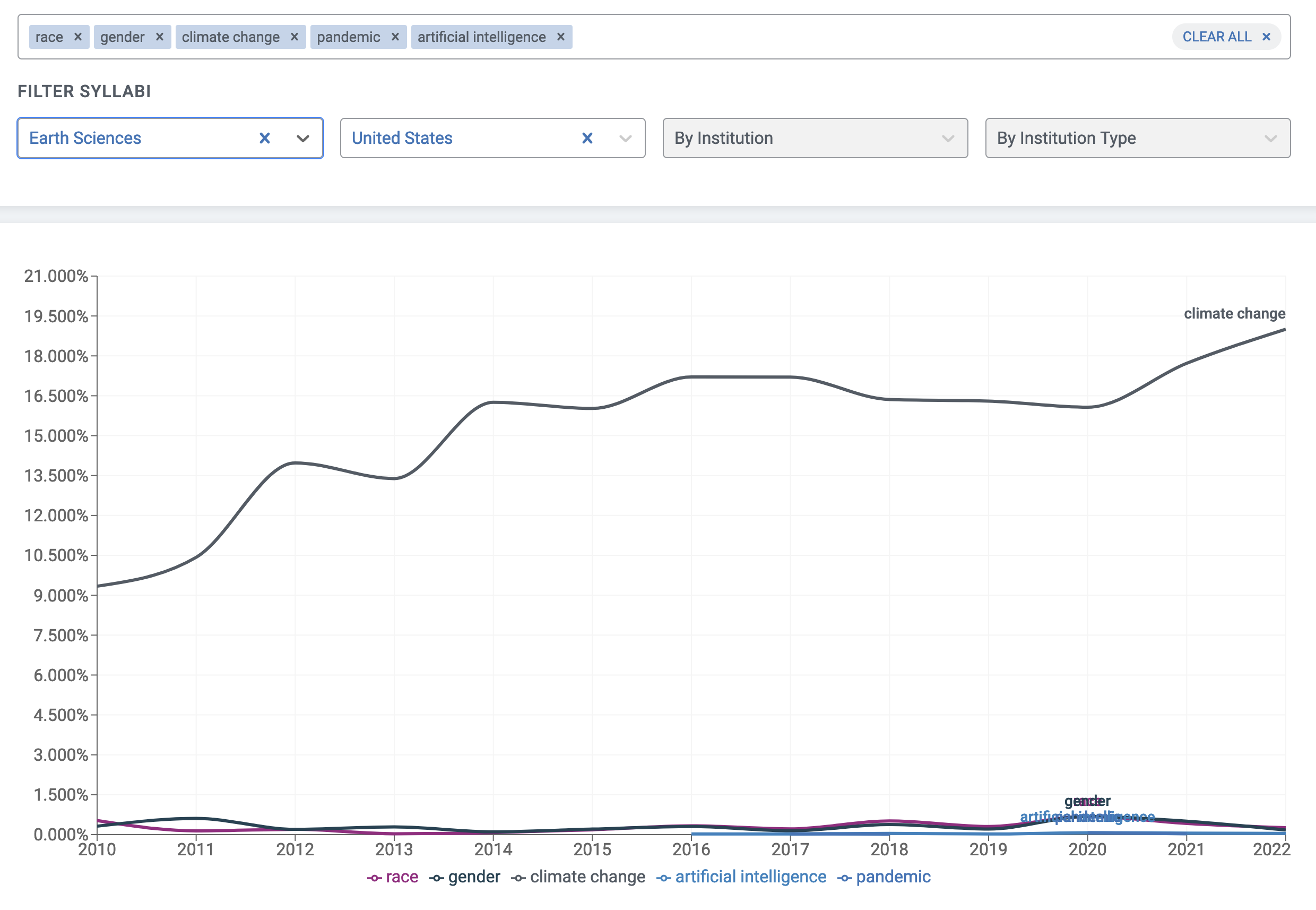

What does it take to really move the needle in a field? I think we can see that to some extent with ‘climate change’ in the Earth Sciences. Around twice as many classes mention climate change in 2022 as in 2010 – but it’s still fewer than 1 in 5! There are still lots of Earth Science classes about other topics.

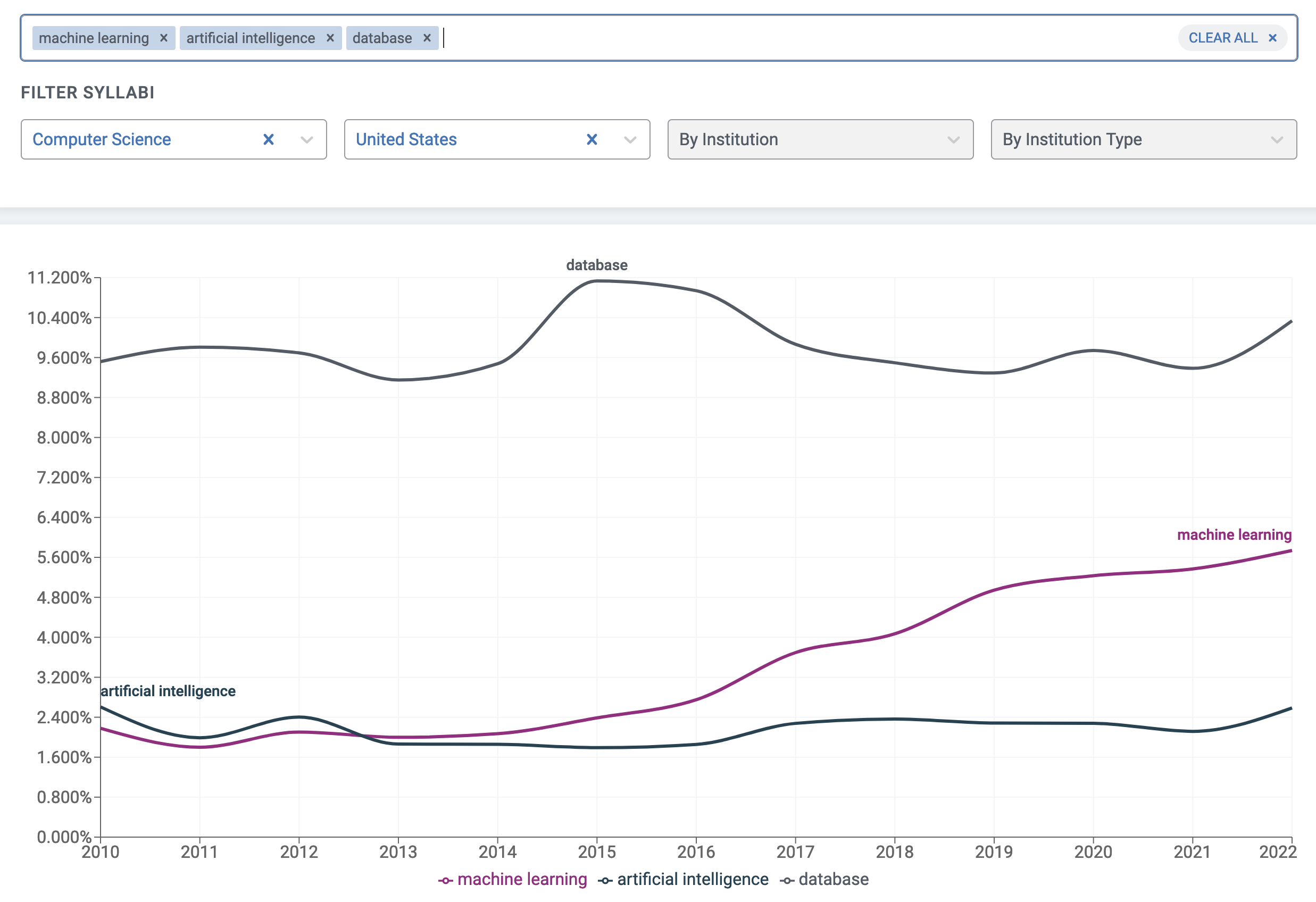

‘Machine learning’ in Computer Science is another example. It has roughly tripled since 2010 but only to around 6% -- still a narrow topic in a large field. ‘Artificial intelligence,’ over this period, is steady state at around 2-3% of classes. We’ll see what 2023 brings.

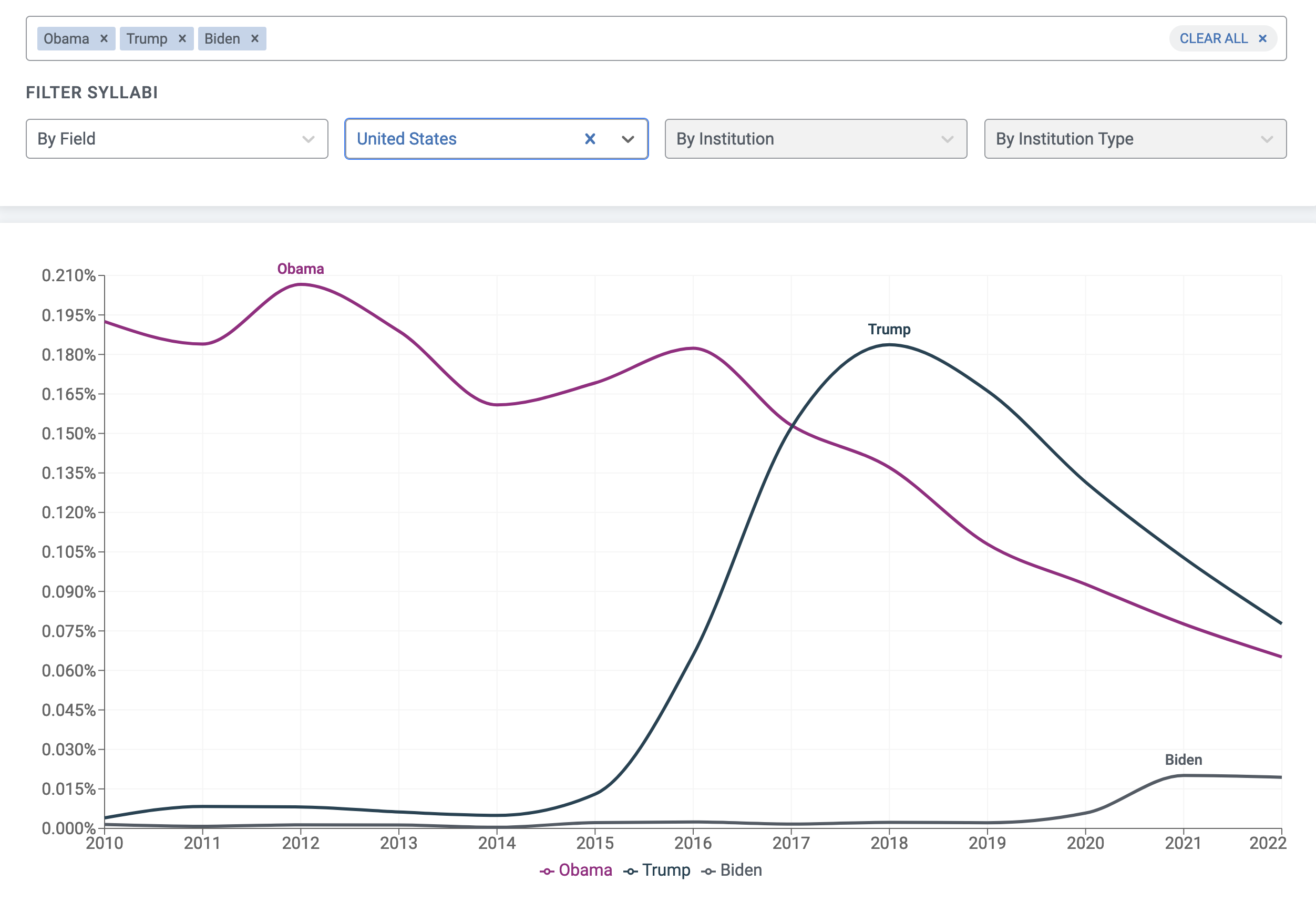

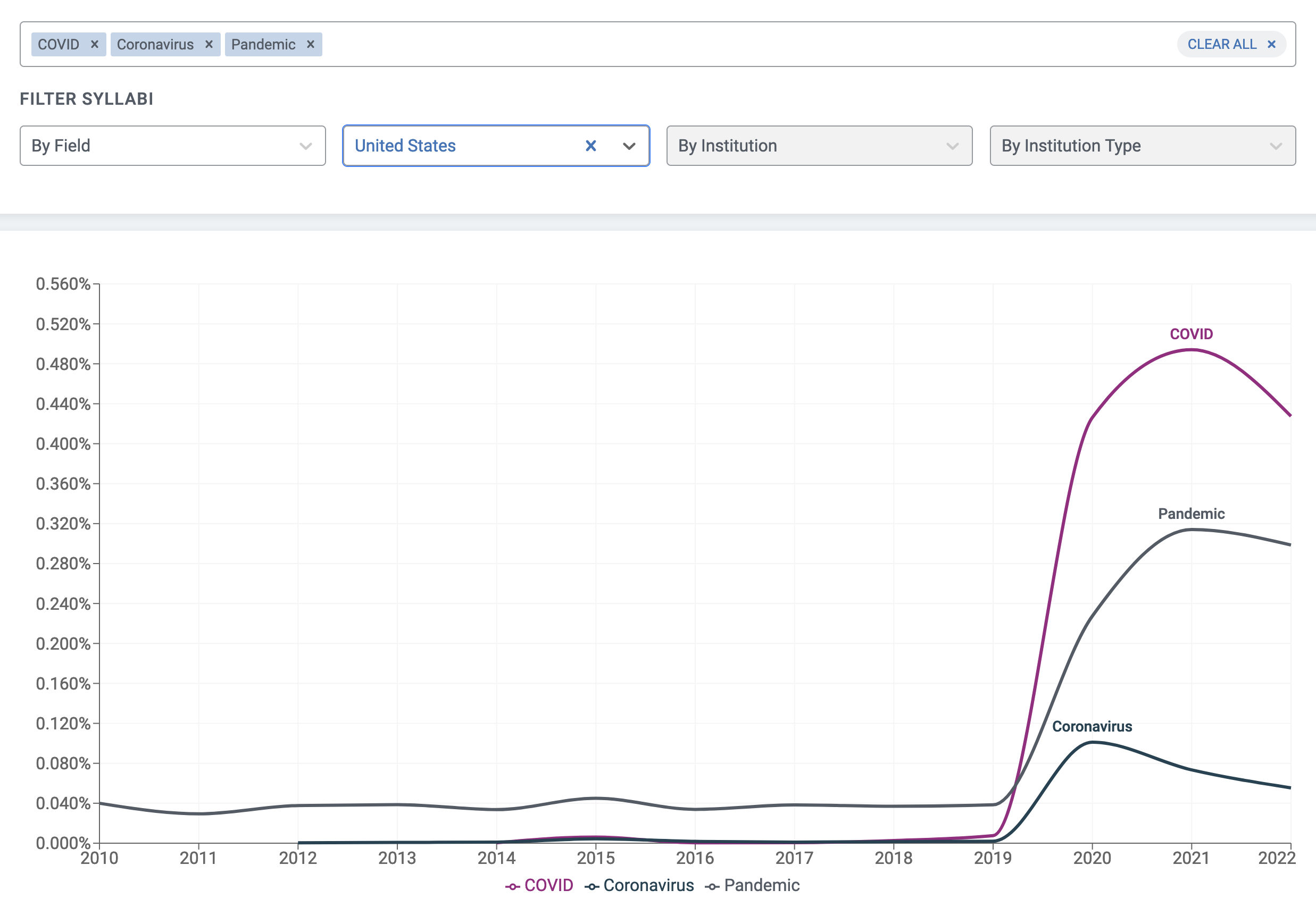

Can we rule out that our data is just insensitive to short term trends? I think so. Presidents and pandemic terms are very-low-frequency terms in the dataset, but they track pretty well with expectations. Covid-related terms would be nearly ubiquitous since 2020 if we included the administrative sections of these documents – but we don’t.

Obviously, singling out a few keywords is a very limited way of looking at the content of the curriculum. One should expect concepts and perspectives to 'spread out' across a wider vocabulary and in ways that are not always explicitly signaled in course descriptions and learning outcomes. But testing with adjacent terms didn’t turn up major divergence from the examples above.

My own experience would attribute more importance to these perspectives on campus and in the lives of students than the course data suggests. At the same time, I think that most public conversations about higher ed rely too heavily on personal experience, elite colleges, and cherry-picked examples that are pretty remote from the experience of most students. One could conclude from our data that students in 2022 are receiving educations that, in rough curricular terms, in most fields, would be hard to distinguish from those in 2010 – and probably earlier in many fields (we generally use 2010 as a starting point for time series views because that’s when our dataset becomes large). Much of this consistency is built into the structure of American higher education, in which change has to diffuse across hundreds of systems, thousands of schools, and generational processes of faculty turnover. In short, if ‘woke’ politics is a force on US campuses, it's hard to see the curriculum as a significant contributing factor, much less a driver of it. You'll have to look elsewhere for explanations.