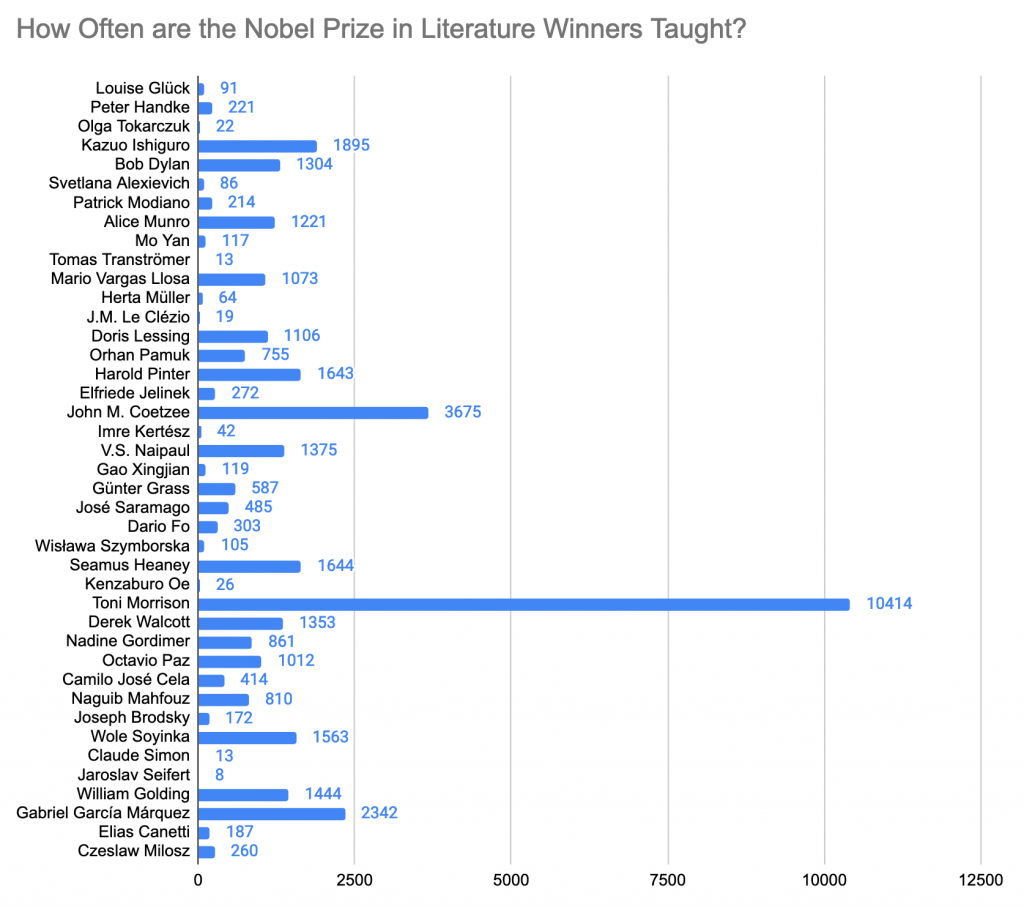

Olga Togarczuk won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2018. She appears on 22 syllabi in the OS dataset. Peter Handke won in 2019 and appears on 221. Louise Glück, who won this past September, appears on 91. These are low numbers (even assuming, in Glück’s case, that we structurally undercount poetry, which we probably do). None of these authors are widely taught. Curious, I spent some time exploring the place of Nobel Prize-winners in the curriculum. The results are pretty striking. Here are the past forty Literature winners.

I’ve struggled somewhat to make generalizations here. There is clearly a lot variation in how often the prize winners are taught, ranging from the ubiquitous Toni Morrison to a whole raft of writers who are almost never assigned. The notions of literary reputation and value that animate the Nobel committee appear to have little connection to the judgements that faculty make in assigning texts. Nor–by all appearances–is winning a prize a guarantee of more teaching attention.

For Nobel watchers, this probably isn’t a surprise. Generations of commentators have written about the byzantine politics of literary reputation and influence that shape the prize, about its varieties of regional and gender bias and more recent politics of outreach, and about the diverse uses of the prize for social and political commentary. There are endless arguments about the uneven judgement of the committee, focused mostly on the literary giants left unrecognized and the winners who were (and remain) obscure. (For an entertaining, polemical summary, see Myer 2007).

These factors surely play some role in the different teaching fates of the winners, but also lead into a thicket of subjective critique. We can perhaps tease out a couple simpler patterns.

Putting aside Morrison’s outlier popularity for a moment, the Anglo-American winners–Ishiguro, Munro, Lessing, Pinter, Heaney, Golding–are pretty well and consistently represented in teaching. Counts between 1000 and 2000 put them in the company of canonical writers like Livy (1800 appearances), Carlyle, (1850), Proust (1594), and Alcott (1612) though not among the highest-scorers that all literature majors and many other students will encounter at least once in their studies.

Non-British European writers, in contrast, account for a lot of Nobel Prizes but are nearly invisible in the curriculum. Only Gunter Grass (the 1998 winner) cracks 500 appearances, and his most assigned title, The Tin Drum, appears only 211 times. None of the other continental European winners–Modiano, Tranströmer, Müller, Le Clézio, Jelinek, Saramago, Fo, Cela, Simon, Seifert, and so on–are likely to be encountered outside the rare regional or country-focused literature class. The two Chinese winners are also rarely taught.

One simple explanation is that the Nobel Prize committee works with a concept of ‘world’ literary culture that has no equivalent in university teaching. Most teaching continues to pass through national traditions, which in our mostly US-based sample favors British and American writers and pushes the study of most other literatures to the edges of the curriculum.

There is, nonetheless, a strong framework for cross-cultural literary comparison in the Nobel results. The ascendancy of post-colonial literary studies is visible throughout, from Coetzee’s 3675 appearances, to Naipaul’s 1375 and Walcott’s 1353; from Vargas Llosa’s 1073 to Paz’s 1012, Soyinka’s 1563, and Garcia-Marquez’s 2342. And arguably through Morrison’s 10,414. The most visible division in the results is between authors who fit easily within a successfully-institutionalized post-colonial teaching enterprise and those (mostly continental European authors) who don’t.

Obviously a handful of prizes provide a limited view of this topic. But there is the beginning of a story here about competing concepts of literary value, their different forms of institutionalization (in the case of post colonial studies across thousands of classes), and the zero-sum nature of the choices they create.